La Svezia, formalmente neutrale, in realtà lasciò che i nazisti attraversassero i suoi confini per spostare truppe e materiali sia in occasione della conquista della Norvegia (Operazione Weserübung), sia in occasione dell’attacco all’Unione Sovietica, per spostare un’intera divisione in Finlandia. Breve nota di Andrea Lonardo

Riprendiamo sul nostro sito un articolo di Andrea Lonardo. Restiamo a disposizione per l’immediata rimozione se la sua presenza sul nostro sito non fosse gradita a qualcuno degli aventi diritto. I neretti sono nostri ed hanno l’unico scopo di facilitare la lettura on-line. Per approfondimenti, cfr. la sezione Novecento: fascismo e nazismo.

Il Centro culturale Gli scritti (16/8/2020)

Non è facile reperire notizie sul web su di un episodio importante della II guerra mondiale. La Svezia era formalmente neutrale e non avrebbe così dovuto appoggiare in nessun modo i nazisti, in realtà, invece, in ben due occasioni permise l’attraversamento dei suoi confini perché i nazisti spostassero truppe e materiali in Norvegia, in occasione dell’Operazione Weserübung per la conquista della Danimarca e della Norvegia e poi, in maniera ancora più clamorosa, quando lasciarono passare sui propri territori addirittura un’intera divisione, la 163esima, guidata dal generale Engelbrecht, con tutto l’equipaggiamento di armi, per attaccare dalla Finlandia la Russia, in occasione dell’Operazione Barbarossa.

Si comprende ancora di più il comportamento profondamente scorretto della Svezia dinanzi al nazismo se lo si confronta con l’atteggiamento di Franco, che pure guidava un regime fascista. La Spagna franchista non consentì alcun passaggio di truppe alla volta di Gibilterra, caposaldo la cui conquista avrebbe significato un passo avanti decisivo nazista nella conquista del Mediterraneo.

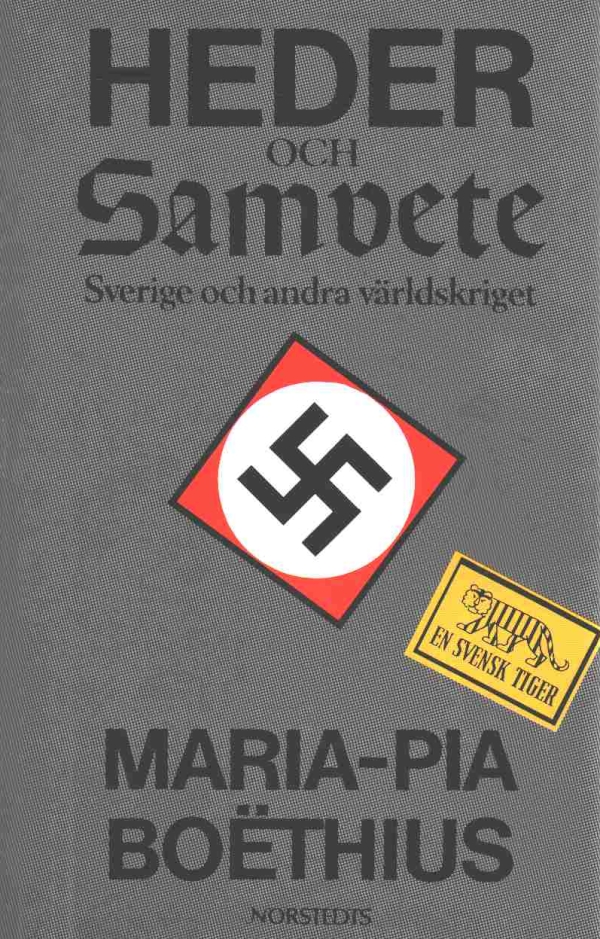

L’atteggiamento “binario” dell’intellighenzia del nuovo secolo appare evidente anche dal silenzio dal quale vengono circondato questi eventi così ambigui della storia svedese, poiché la Svezia è oggi una socialdemocrazia intoccabile dalla cultura. È possibile reperire solo a fatica alcuni testi in inglese, come questa voce da Wikipedia, mentre l’importante libro di Maria-Pia Boëthius, Heder och Samvete, (Onore e coscienza), scrittrice svedese che ha avuto il merito di sollevare la questione, è stato ignorato in Italia e non è possibile leggerlo in traduzione.

Ovviamente la Finlandia era ancor più coinvolta e sebbene non fu mai formalmente alleata del nazismo, essa fu, però, “co-belligerante” con la Germania del Reich, secondo la dicitura dell’epoca.

Qui la voce di Wikipedia in inglese (ne esiste anche la versione francese) Transit of German troops through Finland and Sweden (qui ripresa al 16/8/2020) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transit_of_German_troops_through_Finland_and_Sweden

Transit of German troops through Finland and Sweden

The matter of German troop transfer through Finland and Sweden during World War II was one of the more controversial aspects of modern Nordic history beside Finland's co-belligerence with Nazi Germany in the Continuation War, and the export of Swedish iron ore during World War II.

The Swedish concession to German demands during and after the German invasion of Norway in April–June 1940 is often viewed as a significant breach with prior neutrality policies that were held in high regard in many smaller European nations. After they were publicly acknowledged, the Soviet Union immediately requested a similar but more far-reaching concession from Finland, which invited the Third Reich to trade similar transit rights through Finland in return for weaponry lacked by the Finns. This was the first significant proof of a changed, more favorable, German policy vis-à-vis Finland, that ultimately would put Finland in a position of co-belligerence with Nazi Germany in the Continuation War against the Soviet Union (25 June 1941 – 4 September 1944).

German troops through Sweden

After Denmark and Norway were invaded on 9 April 1940, Sweden and the other remaining Baltic Sea countries became enclosed by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, then on friendly terms with each other as formalized in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The lengthy fighting in Norway resulted in increased German requests for indirect assistance from Sweden, demands that Swedish diplomats were able to fend off by reminding the Germans of the Swedes' feeling of closeness to their Norwegian brethren. With the conclusion of hostilities in Norway this argument became untenable, forcing the Cabinet to give in to German pressure and allow continuous (unarmed)[citation needed] troop transports, via Swedish railroads, between Germany and Norway.

The extent of these transports was kept secret, although spreading rumors soon forced prime minister Per Albin Hansson to admit their existence. Officially the trains transported wounded soldiers and soldiers on leave (permittent-tåg), which would still have been in violation of Sweden's proclaimed neutrality.

In all, close to 100,000 railroad cars had transported 1,004,158 military personnel on leave to Germany and 1,037,158 to Norway through Sweden by the time the transit agreement was disbanded on 15 August 1943[1].

After the German invasion of the Soviet Union in early summer of 1941, Operation Barbarossa, the Germans on 22 June 1941 asked Sweden for some military concessions. The Swedish government granted these requests for logistical support. The most controversial concession was the decision to allow the railway-transfer of the fully armed and combat-ready 163rd Infantry Division from Norway to Finland.

In Sweden the political deliberations surrounding this decision have been called the "midsummer crisis". Research by Carl-Gustaf Scott argues however that there never was a "crisis", and that "the crisis was created in historical hindsight in order to protect the political legacy of the Social Democratic Party and its leader Per Albin Hansson."[2]

Soviet troop transfers through Finland

The Moscow Peace Treaty that ended the Winter War in March 1940 required Finland to allow the Soviet Navy to establish a naval base on the Hanko Peninsula, at the entrance to the Gulf of Finland. The treaty didn't contain any provisions for troop and material transfer rights, and Finland's leadership was left with the impression that the Soviet Union would supply the base by sea.

On 9 July, two days after Sweden had officially admitted to having granted transfer rights to Germany, Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov demanded free transfer rights through Finland, using Finnish Railways. In the ensuing negotiations the Finns were able to limit the number of Soviet trains simultaneously in Finland to three. An agreement was signed on 6 September.

German troop transfers through Finland

In the summer of 1940, Nazi Germany's occupation of Norway brought to the fore the need to transfer troops and munitions not only by sea, but also through the neutral countries of Sweden and Finland. The most convenient route to northernmost Norway was a rough truck road that passed through Finland. Diplomatic relations between Finland and the Third Reich improved after the Winter War, when Germany had sided with the Soviet Union, and on 18 August an agreement was reached that allowed Germany to set up supporting bases along the long Arctic truck road. The negotiations were carried out between the Finnish military leadership and Hermann Göring's personal emissary Josef Veltjens. The agreement was kept secret until the first German troops arrived in the port of Vaasa on 21 September.

The German transfer rights were in breach of, if not the letter, then the spirit of the Russo-Finnish Moscow Peace Treaty, as well as the Russo-German Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, but the Finns greeted the agreement as a balance against the increasing pressure from the Soviet Union. The transit road through northern Finland had a significant symbolic value, but in transit volume it was of lesser significance until the run up to Operation Barbarossa, when the route was used to deploy five Wehrmacht divisions in northern Finland.

Timeline

9 April 1940

Germany invades Denmark and Norway

Sweden accepts German demands for import and export of products to/from Norway as before—i.e., no war material.

16 April 1940

Food and oil supplies permitted transport to northern Norway to "save the population from starvation" after the war had emptied the reserves.

Troops, including 40 "red-cross soldiers" were denied transit.

18 April 1940

The 40 "red-cross soldiers" were accepted for transit together with a train loaded with sanitary material. However, when this turned out to contain 90% food, according to the Swedish customs, further requests for transit of "sanitary material" were rejected.

April to June 1940

Norway protests that Sweden is taking the neutrality too seriously, expecting more support for Norway.

German civil sailors were given individual transit visas.

Wounded soldiers were transported through Sweden, and 20 further "red-cross soldiers" and a physician were allowed to pass together with five wagons with food.

18 June 1940

As the war in Norway concluded, German demands for transit were repeated with greater emphasis. The Swedish parliament did formally modify the neutrality policy according to the German demands. (The United Kingdom and France were informed before the parliament debate.)

7 July 1940

Sweden's Prime Minister admits the transit in a public speech in Ludvika.

8 July 1940

Swedish agreement with Nazi Germany formalized:

1 daily train (500 man) back and forth Trelleborg–Kornsjø.

1 weekly train (500 man) back and forth Trelleborg–Narvik.

The agreement with Germany was later expanded.

9 July 1940

The Soviet Union demands troop transfer rights through Finland.

15 July 1940

Protests from Norway's exile Cabinet, and from the United Kingdom's government, against Swedish concessions for German demands.

August 1940

After the Soviet occupation of the Baltic Republics, they are annexed to the Soviet Union, making the Soviet Union a dominant power at the Baltic Sea beside the Third Reich.

18 August 1940

A German envoy agree on troop transfer rights with Finland's leadership:

The Wehrmacht is granted rights to use

the ports of Vaasa, Oulu, Kemi, and Tornio.

rail lines from the ports to Ylitornio and Rovaniemi.

roads from Ylitornio and Rovaniemi to northern Norway, and to establish depots along the roads.

The agreement was later expanded to include the port of Turku.

6 September 1940

The troop transfer treaty between Finland and the Soviet Union is signed:

The Soviet Union can use rail lines from the Soviet border to Hanko.

Only three trains are allowed to be simultaneously in Finland.

April 1941

As the German plans for an attack on Russia were taken seriously by the Swedish government, it was discussed between the Cabinet and the Commander-in-chief how Sweden could react in case of a war between Germany, Finland and Russia.

The Commander-in-chief warned of the danger of a continued policy of neutrality, which could provoke German anger and occupation. Plans for cooperation with Germany and Finland were made.

Individual Cabinet members considered cooperation with the Soviet Union, however this was fiercely rejected by a large cabinet majority.

Midsummer 1941

In connection with Germany's attack on Russia on Midsummer's Day 1941, Sweden had its most serious cabinet crisis:

22 June 1941, with Operation Barbarossa the German invasion of the Soviet Union starts.

Germany demanded to transit the fully armed Division Engelbrecht (163. Inf. Div) from Norway to Finland.

23 June 1941

The Cabinet discuss the requested transit of one armed division (Division Engelbrecht) from northern Norway to northern Finland. Agrarians, Liberals and the Right supported acceding to the combined Finnish-German request. Some Social Democrats opposed it.

The king declared "he would not be a party of giving a negative answer to Finland's and Germany's request", which was tactically cited by the prime minister in terms of a threat of abdication. It has not been decisively shown whether the prime minister's interpretation was purely tactical, or if he in fact had perceived an honest intention to consider abdication on the part of the king, but the prime minister's record and personality speak for the tactical-theory.

24 June 1941

The Social Democratic parliament group decides, with the votes 72-59, to try to convince the other parties for a rejection, but to agree in case they insisted.

The other parties seemed prepared to split the Cabinet.

25 June 1941

The Swedish government accepts the transit of Division Engelbrecht.

25 June 1941

Soviet Union stages a major air assault with 460 planes against Finnish targets.

Finnish government issues a statement that Finland is at war, later called the Continuation War.

9 July 1941

The German Troop transports Tannenberg, Preussen, and Hansestadt Danzig are sunk by Swedish mines in Swedish waters outside southern Öland. 200 Germans drowned.

11 July 1941

Finland's official ambitions for a Greater Finland become known abroad with the publication of Mannerheim's Order of the Day of 10 July, the so-called Sword Scabbard Declaration.

New demands on transit of an armed division from Trelleborg to Tornio.

following weeks of July 1941

Public attitudes in Sweden to Finland's and Germany's demands grew less and less favorable.

Troop transit is proposed in Swedish waters along the Swedish coast with Swedish escort.

autumn of 1941

Several requests for neutrality-violating exports and transits are rejected during the following autumn.

In 1943, as Germany's prospects began to wane, Swedish public opinion turned against the agreement, and pressure from Britain and the USA mounted, the Swedish Cabinet declared on 29 June 1943 that the transits had to stop before October 1943. On 5 August it was officially announced that the transits were to cease[3].

Note al testo

[1] Sveriges militära beredskap 1939–1945 [Swedish Military Preparedness 1939–1945] (in Swedish). Kungl. Militärhögskolan Militärhistoriska avd. 1982. p. 498. ISBN 91-85266-20-5.

[2] From the abstract of: Carl-Gustaf Scott, "The Swedish Midsummer Crisis of 1941: The Crisis that Never Was" Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 37, No. 3, 371–394 (2002) (SAGE JOURNALS ONLINE).

[3] "Transiting" (in Norwegian). NorgesLexi.com. http://mediabase1.uib.no/krigslex/t/t3.html#transittering Archived 2010-01-05 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2008-08-30.