I/ Andrea Lonardo. Narrare la storia dell’arte - Narrare la storia della Chiesa II/ Andrea Lonardo. “Narrating the History of Art - Narrating the History of the Church”

- Tag usati: english_texts, scritti_andrea_lonardo

- Segnala questo articolo:

Riprendiamo sul nostro sito il testo di una relazione tenuta il 30 aprile da Andrea Lonardo al Convegno di Pietre vive, organizzato presso la Cappella Universitaria de La Sapienza di Roma. La traduzione inglese è stata curata da Nicola Tassinari. Restiamo a disposizione per l’immediata rimozione se la presenza sul nostro sito non fosse gradita a qualcuno degli aventi diritto. I neretti sono nostri ed hanno l’unico scopo di facilitare la lettura on-line. Per approfondimenti. cfr le sezioni Arte e fede e Roma e le sue basiliche.

Il Centro culturale Gli scritti (15/5/2016)

I/ Andrea Lonardo. Narrare la storia dell’arte - Narrare la storia della Chiesa

1/ Che rapporto c’è tra la storia dell’arte e la storia (della Chiesa). L’opera d’arte e l’opera d’arte cristiana è strumento di potere o espressione di vita?

Quali narrazioni vengono fatte oggi dalle guide che accompagnano turisti e pellegrini? Quale visione emerge dalle loro parole del rapporto fra storia dell’arte e storia della Chiesa?

A/ Esiste certamente una narrazione spiritualistica dell’arte, quando alcune comunità cristiane preparano strumenti molto “bigotti” che invitano a passare dal battistero di San Giovanni al Laterano al ricordo del Battesimo e alla professione di fede, dalla Cattedra petrina al ringraziamento per la presenza del pontefice.

B/ Ma esiste ancor più una presentazione artistica tutta basata su datazioni storiche e considerazioni filologiche, secondo i criteri della cultura dominante che rifiuta di affermare che cosa è un “classico” e quali sono i “valori” umanistici. Per paura di non essere scientifica, spesso una guida oggi si limita a presentare cronologie di edifici ed opere dai tempi della Roma imperiale al presente.

Spesso, però, queste narrazioni così scientifiche per divenire interessanti, per toccare in qualche modo l’immaginazione del pellegrino o del turista, narrano poi risvolti sessual-piccanti (come le favole sulle modelle di Caravaggio o, in età barocca, i racconti su Olimpia Maidalchini, la Pimpaccia) o narrano moralisticamente la corruzione dei papi (da Alessandro VI a Giulio II a Urbano VIII o Alessandro VII), con riferimenti continui all’Inquisizione o insinuando l’idea che l’arte cattolica sia una propaganda, ad esempio, in età barocca utilizzata per una “reconquista” delle perdite avute con la Riforma protestante.

Il passaggio inconscio da un linguaggio scientifico ad uno moralistico è indice del predominio di una visione ideologica scientista e moralista allo stesso tempo.

C/ Esiste anche una narrazione che vede l’artista singolo come libero pensatore, come genio ribelle incompreso in un’epoca oppressiva (così vengono presentati abitualmente, ad esempio, Michelangelo o Caravaggio). Esiste cioè una narrazione che, ancora una volta, separa l’opera d’arte dalla vita del proprio tempo perché non vuole riconoscere la grandezza e la bellezza di una data epoca (sia essa il medioevo o l’età controriformista o l’età barocca).

Spesso dietro questa visione emerge un’idea mai apertamente confessata e cioè che la storia della Chiesa sia stata bella solo fino a Costantino e solo dopo il Concilio: il resto sarebbe un vuoto senza Cristo e senza Spirito.

Ma, ancora più profondamente, dietro questo modo di narrare la storia dell’arte è evidente la dipendenza da una lettura materialista della storia. Tutto viene riferito a questioni di potere, di “propaganda”, con punti di vista imposti dalla classe dirigente ed ecclesiastica del tempo. Tutto viene riletto in una dinamica di conquista dello spazio pubblico tramite l’arte.

La via pulchritudinis implica che si rinunci a questa considerazione dell'opera d'arte come mera sovra-struttura di una sottostante struttura economica o comunque di potere che ne sarebbe il significato portante. Come è noto, questa è l'impostazione materialista, secondo la quale non si darebbe nemmeno la possibilità di una “via della bellezza”, poiché la cultura sarebbe semplicemente la copertura ideologica che verrebbe creata in ogni epoca ad avvallare un determinato rapporto di potere.

Non avrebbe, infatti, alcuna bellezza un'opera d'arte che celasse semplicemente, anche se non intenzionalmente, finalità diverse dalla bellezza stessa. In particolare è stato Ricoeur a classificare sotto il titolo di “maestri del sospetto” i tre grandi maîtres à penser del nostro tempo, Marx, Freud e Nietzsche. Essi sono stati capaci, ognuno dal proprio punto di vista, di “sospettare” di ogni espressione umana, scandagliando in essa ciò che deriva da una lotta di potere soggiacente – così Marx –, da un inconscio che si radica nei rapporti parentali primari, in particolare nel vissuto sessuale – così Freud –, o ancora da una creatività super-ominica che cerca di conferire significato all'universo intero che ne è invece in se stesso nihilisticamente privo – così Nietszche. Se la loro critica decostruttiva rimane un compito ineludibile, resta nondimeno la questione se tutto possa essere ridotto a tali intenzioni spurie e, ancor più, se l’opera dell’uomo – e l’opera d’arte in specie – non nasca piuttosto da un desiderio di bene e di bellezza originari.

Se, nella presentazione di singole opere d'arte o di interi periodi artistici, prevalgono impostazioni che si rifanno a visioni similari, l'opera d’arte verrà allora scandagliata alla ricerca di indizi che mostrino come essa sia stata uno strumento di potere, oppure un oggetto volto a manifestare la vanità del committente, laico od ecclesiastico che l’ha ordinata: l'intera produzione artistica di un dato periodo verrà conseguentemente connotata come propaganda adatta per imporre una determinata visione del mondo ai contemporanei.

La narrazione della “bellezza” postula, invece, un differente presupposto. Il Vangelo si mostra nelle opere d’arte, siano esse capolavori o manufatti più popolari, perché la fede personale ed ecclesiale ha l’esigenza nativa di esprimersi.

La bellezza si produce perché l’incontro con il Cristo non può non manifestarsi, divenendo non solo parola, ma anche affresco, composizione musicale, edificio, suppellettile liturgica, che rimandi creativamente alla fede. Non vi è altra radice ultima della produzione artistica cristiana. Certo possono intervenire nella storia fattori sovra-strutturali, come quelli denunciati dai “maestri del sospetto”, ma essi non potranno mai essere l’elemento determinante dell’iconografia cristiana ed in posizione relativa dovranno restare nella presentazione storico-artistica e nell’utilizzo catechetico delle opere stesse.

Con grande sapienza F. Boespflug ha affermato in merito: «Non ho mai creduto alla teoria del bisogno, fondata su un'opposizione fra autorità e fedeli. [...] Credo molto più a ciò che definirei il dinamismo espressivo delle forti intuizioni. Una religione vissuta in modo intenso da una civiltà deve essere espressa. E dopo le parole, il cristianesimo ha conquistato in modo logico altri registri espressivi, dalle arti plastiche al teatro, dalla musica alla letteratura».

Si vede, già da questo primo accenno, che ogni “guida” deve padroneggiare la storia della Chiesa, per presentarne la grandezza, altrimenti il suo messaggio resterà incompreso.

Si potrebbe dire che, spesso, la fede non si annunzia in maniera diretta: la fede si annunzia in maniera indiretta, nella visione di vita che sorge da essa. La verità della fede si manifesta nella sua capacità di generare, di fecondare. L’espressione artistica è una delle prove della verità del cristianesimo, insieme alla liturgia, alla teologia, alla carità, al matrimonio, all’more che educa i figli, alla passione per il cosmo e così via.

2/ Il momento fondativo: i primi secoli, l’arte paleocristiana e Costantino

La centralità di questa questione appare con evidenza nell’analisi – e nelle diverse interpretazioni - del momento fondativo dell’arte cristiana.

L’esigenza espressiva della fede è così nativa che si manifesta ben prima della svolta costantiniana. Basti pensare che già agli inizi del III secolo – un secolo prima di Costantino - è documentato il possesso di cimiteri da parte della comunità cristiana. A Roma, dove le fonti soccorrono in questo caso la ricerca, Callisto, allora diacono, venne incaricato da papa Zefirino della custodia delle catacombe oggi dette di San Callisto. La comunità, pur essendo perseguitata da pubbliche leggi statali, possedeva già delle proprietà comuni. L’iconografia cristiana dei sarcofagi e degli affreschi catacombali si andava già formando.

Pur essendo difficile datare il passaggio dalle domus ecclesiae alle prime vere e proprie chiese, la costruzione e la decorazione di edifici appositamente cristiani è già un fatto alla metà del III secolo, come è attestato dall’Editto di Gallieno del 262 detto anche Editto di restituzione, proprio perché l’imperatore stabilì che fossero restituite ai cristiani le proprietà che ovviamente dovevano già aver posseduto precedentemente. Un solo edificio cristiano di quel periodo è sopravvissuto, conservato pressoché integralmente: è la famosa chiesa di Dura Europos, nell’odierna Siria. Quella città fu abbandonata nel 256, a motivo dell’arrivo dei Sassanidi e, quindi, tutti i suoi monumenti superstiti sono anteriori a quella data.

Le fonti letterarie mostrano che il caso di Dura Europos non era certamente l’unico. In Eusebio di Cesarea si ha notizia dell’imperatore Aureliano (270-275) che, alla deposizione del vescovo scismatico Paolo di Antiochia, assegnò la chiesa che era sede episcopale a Domno, vescovo cattolico. In documenti dell’Africa latina relativi alla persecuzione di Diocleziano è attestato che ad Abthugni (oggi in Tunisia) e Cirta (nell’antica Numidia, oggi in Algeria) c’erano già, prima del 303, basilicae cristiane.

Nella stessa Roma, quando vi arrivò dall’Africa Vittore, primo vescovo donatista inviato nell’urbe tra il 314 ed il 320, le fonti attestano che, mentre questi non aveva alcuna basilica nella quale riunire i fedeli, la chiesa cattolica ne aveva ben quaranta.

Nell’opera di Lattanzio si afferma addirittura che, al momento dello scatenarsi della persecuzione di Diocleziano, esisteva già da tempo una basilica che era visibile dal palazzo imperiale di Nicomedia, segno che la presenza di edifici cristiani era un fatto ormai normale.

Se la cura degli edifici cristiani e della loro decorazione precede certamente la svolta costantiniana, non meno interessante è il fatto che essa non venga mai a decadere, nemmeno in movimenti ecclesiali che vollero sottolineare il carisma della povertà. È noto, ad esempio, che non solo Francesco d’Assisi si dedicò al restauro architettonico di chiese abbandonate e in rovina - vedi San Damiano in primis - ma anche che volle che le suppellettili liturgiche fossero di materiale prezioso e non vile: «Vi prego, più che se riguardasse me stesso, che, quando vi sembrerà conveniente e utile, supplichiate umilmente i chierici che debbano venerare sopra ogni cosa il santissimo corpo e sangue del Signore nostro Gesù Cristo e i santi nomi e le parole di lui scritte che consacrano il corpo. I calici, i corporali, gli ornamenti dell’altare e tutto ciò che serve al sacrificio, debbano averli di materia preziosa. E se in qualche luogo il santissimo corpo del Signore fosse collocato in modo troppo miserevole, secondo il comando della Chiesa venga da loro posto e custodito in un luogo prezioso, e sia portato con grande venerazione e amministrato agli altri con discrezione».

Questi fatti attestano che l’esistenza di un’arte cristiana ha una radice diversa dall’aspirazione al potere.

3/ Ogni artista esprime non solo se stesso, ma l’intero suo periodo: parlare della grandezza di un artista vuol dire anche parlare della grandezza della Chiesa del suo tempo che lo apprezzava

Sempre si ripete ciò che avvenne fin dalle origini, prima di Costantino, e poi con lui. Nel medioevo, in maniera suprema, le grandi chiese romaniche o gotiche sono opera di un popolo.

Un autore anti-cristiano, Dario Fo, ha cercato di dimostrare che il Duomo di Modena sia sorto in un periodo in cui non c’era né il re, né un vescovo, per cercare di nascondere il fatto che sempre il popolo ha amato le sue cattedrali e che sempre nel medioevo nelle cattedrali si ponevano attori e buffoni, santi e letterati, uomini e donne, sibille e profeti, cavalieri e dame, segni zodiacali e ricerca scientifica dell’uomo, diavoli e draghi, e così via.

Per questo parlare del Duomo di Modena non vuol dire parlare di un’eccezione, bensì della bellezza del medioevo, non di una eccezione anti-cattolica!

Allo stesso modo parlare di Michelangelo Buonarroti vuol dire parlare di un uomo che, fino al giorno della sua morte, ha lavorato per onorare la memoria di Giulio II (la tomba che è il Mosè), per onorare l’importanza della Legge e dei ministri inviati da Dio (i comandamenti e Mosè stesso), così come ha lavorato al tamburo della cupola di San Pietro, senza voler essere pagato, così come ha lavorato alla decorazione della Cappella Paolina, la Cappella destinata all’adorazione eucaristica dei papi.

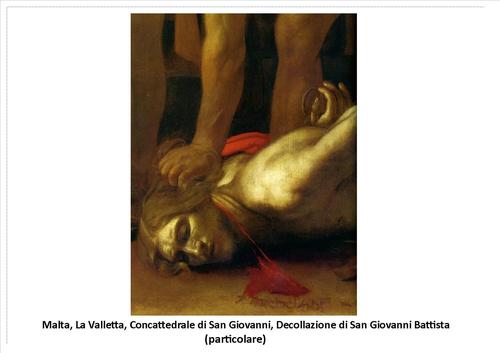

Allo stesso modo parlare di Caravaggio vuol dire esaltare l’età della controriforma. Il Merisi amava Roma e, fuggito per l’omicidio, fece di tutto per ritornarvi. A Malta si fece cavaliere crociato, con l’assenso del papa, firmandosi frater “consacrato”.

Eppure, ingannando gli ascoltatori, le guide continuano a ripetere del rifiuto delle sue opere (cfr. la Madonna della serpe, con la sua centralità mariana), attribuiscono ogni dato cattolico a contingenze politiche (cfr. l’inserzione della figura di Pietro nella Vocazione di San Matteo), tacciono della centralità della Scrittura nella Chiesa controriformista (l’evangelista Matteo), dimenticano di ricordare delle devozioni che egli ritraeva (la casa di Loreto nella Vergine dei Pellegrini), trascurano le evidenti citazione non solo di Michelangelo Buonarroti (cfr. la Cappella Cerasi, che è una Cappella Paolina in miniatura), ma anche dei maestri dell’umanesimo e del rinascimento (cfr. la Vergine del Parto di Jacopo Sansovino in Sant’Agostino in Campo Marzio).

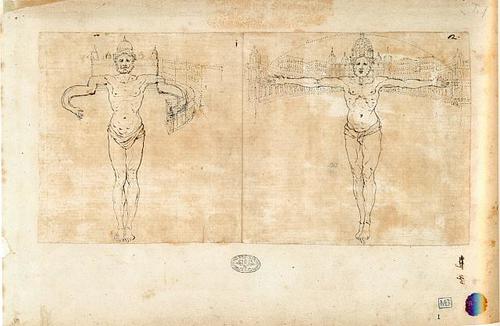

Allo stesso modo nel trattare il barocco le guide omettono di spiegare la sua funzione ed il perché delle sue scelte artistiche. Evidente è, a questo riguardo, il senso del colonnato di San Pietro (ma, in fondo, dell’utilizzo insistito della linea curva, concava o convessa). Alcuni schizzi coevi mostrano la consapevolezza degli uomini dell’età barocca del suo significato simbolico. Lo stesso papa Alessandro VII che commissionò il colonnato scrisse che esso voleva ricordare due braccia che «accolgono i cattolici per confermarli nella fede, gli eretici per riunirli alla Chiesa, gli infedeli per illuminarli» (cfr. il bellissimo Lo spirito del barocco di Olivier de la Brosse O.P. su www.gliscritti.it ).

4/ Ogni opera trae luce dalla sua posizione storico-geografica e dalla sua funzione liturgica

La collocazione storica dell’opera d’arte si fonda a sua volta sulla narrazione di ciò che non caratterizza solo una determinata epoca della storia della Chiesa, ma permane nel tempo come una costante nella fede e nella vita della Chiesa.

La Chiesa, infatti, è una realtà pubblica fatta di uomini e donne che comunicano fra di loro e con gli uomini attraverso segni: senza l’utilizzo di segni adeguati la salvezza si ridurrebbe ad evento privato senza alcuna consistenza ecclesiale.

Nell’utilizzare la via pulchritudinis, dobbiamo affrontare la grande obiezione che l’uomo moderno rivolge al cristianesimo. L’allora cardinale Ratzinger l’ha enunziata in questi termini:

«Per noi uomini di oggi lo scandalo fondamentale dell’essere-cristiano è rappresentato innanzitutto dall’esteriorità in cui l’esperienza religiosa sembra finita. Ci scandalizza il fatto che Dio debba esser comunicato mediante apparati esteriori: tramite la chiesa, i sacramenti, il dogma, o anche solo tramite la predicazione (kerygma), dietro la quale ci si ripara volentieri per attenuare lo scandalo, ma che resta egualmente qualcosa di esterno. Di fronte a tutto ciò, ci si chiede: Dio abita proprio nelle istituzioni, negli eventi o nelle parole? L’Eterno non tocca forse ciascuno di noi interiormente? Orbene, a questo interrogativo bisogna rispondere subito e con semplicità in maniera affermativa e aggiungere: se esistesse soltanto Dio e una somma di singoli, il cristianesimo non sarebbe necessario. [...] Per la salvezza del singolo semplicemente non ci sarebbe stato bisogno né di una chiesa, né di una storia della salvezza, né di una incarnazione e passione di Dio nel mondo».

L’uomo è una persona dotata non solo di una natura spirituale, ma anche di una corporeità che lo costituisce come essere in relazione. Per questo non avrebbe alcun senso per lui una religione che fosse puramente interiore. Lo stesso Ratzinger così affronta la questione:

«L’essere nella corporeità include necessariamente anche la storia e la vita comunitaria, giacché, se il puro spirito può essere pensato come rigorosamente a sé stante, la corporeità attesta il derivare da altri: gli uomini vivono l’uno dell’altro, in un senso quanto mai reale e al contempo pluristratificato».

L’arte ci mostra in maniera peculiare tutto questo. Le grandi realizzazioni artistiche sono quasi sempre avvenute con il concorso dell’intero popolo di Dio. Si pensi, solo per fare un esempio, ai grandi cantieri delle cattedrali romaniche e gotiche. Recenti studi sugli archivi della Fabbrica del Duomo di Milano, ad esempio, hanno evidenziato come al suo finanziamento contribuirono non solo le grandi famiglie del tempo, ma ancor più i singoli fedeli, finanche le categorie apparentemente più marginali della comunità, come molte prostitute del tempo che, liberamente, versarono le loro offerte per l’erezione della cattedrale ambrosiana.

Non dobbiamo mai dimenticare che i turisti/pellegrini vedono le nostre chiese nei momenti in cui esse sono vuote e non ne percepiscono l’utilizzo nelle grandi liturgie.

Raccontare del colonnato di San Pietro vuol dire allora raccontare delle elezioni e dei funerali dei pontefici, delle benedizioni e delle udienze. Dove potremmo altrimenti, senza il colonnato o la basilica, ricevere l’annunzio dell’Habemus papam e la prima benedizione? Dove potremmo ordinare i nuovi preti? Dove celebrare il Battesimo dei catecumeni? Ma, allo stesso modo, come sarebbe stato possibile salvare tanti ebrei e rifugiati senza quei luoghi? E chi ancora avrebbe potuto mediare fra nazisti e alleati perché non si combattesse a Roma, senza l’esistenza stessa dello Stato della Città del vaticano (cfr. il 4 giugno 1944)?

Similmente quel Baldacchino del Bernini, che viene sempre stupidamente ricordato con la pasquinata Quod non fecerunt Babari fecerunt Barberini, non dovrebbe essere ricordato, invece, per la straordinaria modalità con la quale attesta per il popolo di Dio la centralità dell’eucarestia (ed anche del Battesimo)?

Si pensi anche all’importanza di “narrare” la collocazione liturgica delle opere stesse. Caravaggio, ad esempio, volle dipingere, “citando” Michelangelo, San Pietro che mentre viene crocifisso si volge a guardare l’eucarestia (Cappella Cerasi e Paolina).

5/ L’importanza dell’immaginazione

Compito della guida è quello di narrare facendo immaginare i luoghi al momento della loro fondazione, o al tempo degli eventi che lì si sono verificato. Gli Esercizi spirituali di Sant’Ignazio e l’esperienza del pellegrinaggio in Terra Santa o nei luoghi francescani hanno creato una tradizione consolidata in questo campo, mostrandoci quale cammino seguire.

Dinanzi a piazza San Pietro, ad esempio, narrare vuol dire assumersi il compito di far immaginare la morte di Pietro e la sua sepoltura, per mostrare la straordinaria bellezza e verità della sua testimonianza. Omettere tale “immaginazione” vuol dire misconoscere tutto il significato del luogo stesso.

In www.giubileovirtualtour.it abbiamo provato ad utilizzare anche le tecniche 3D per dare forza a questa esigenza di immaginare (cfr. anche La basilica di San Pietro in Vaticano: guida per la visita. I testi di www.giubileovirtualtour.it, di Andrea Lonardo).

La piazza di San Pietro è il luogo per fare “immaginare” il suo martirio, ma anche l’elezione del papa che da essa trae vita e senso. Per un pellegrino straniero è decisivo “capire immaginando” ciò che tante volte ha già visto in televisione, passando dal virtuale al reale. Il luogo aggiunge a ciò che egli già sa l’hic: qui, in questo luogo, dinanzi a te.

Non dobbiamo dimenticare che siamo chiamati a raccontare l’origine del cristianesimo, o l’annuncio del Vangelo in un dato luogo, o la storia di un santo (l’“antico” Agostino o le “moderne” santa Teresa del Bambino Gesù o Madaleine Delbrel).

Io presento in Roma la storia del cristianesimo attraverso i Fori Romani e il Palatino, senza limitarmi alle semplici chiese (cfr. Spiegare il Nuovo Testamento passeggiando per il Palatino ed i Fori imperiali. Una guida per la visita, di Andrea Lonardo).

6/ Vincere la tentazione del politicamente corretto e dire una parola su come la storia di cui parliamo ha cambiato la storia dei paesi dove viviamo

Una narrazione della storia dell’arte secondo i criteri del politicamente corretto vigente nasconde molti elementi storici per paura di sembrare intollerante verso i non cattolici o comunque verso i non credenti. Solo del cristianesimo è abitudine parlare male!

Si tace addirittura che Van Gogh fu un predicatore protestante e che si conserva la sua prima omelia.

Si tace che Johannes Vermeer fosse un fervente cattolico costretto ad abitare nel ghetto papista di Delft e che a lui, come ai membri della Chiesa cattolica, fosse proibito al tempo celebrare la messa in pubblico, disconoscendo il valore “cattolico” di molte sue opere (cfr. il Trionfo della fede”). In Svezia la messa cattolica sarà permessa solo a partire dal 1951.

Si tace che, mentre si sviluppava il teatro dell’età barocca in Italia, l’Inghilterra puritana vietasse i teatri, radendoli al suolo, e distruggesse gli strumenti musicali (il teatro e la musica erano ritenuti demoniaci), o che nei Paesi Bassi fosse vietato dalla sinagoga di Amsterdam agli ebrei di parlare con Spinoza dichiarato eretico dai rabbini (1656).

Andando più indietro nella storia si tace del fatto che in Inghilterra, a partire da Enrico VIII, tutti i conventi ed i monasteri siano stati requisiti e distrutti, con l’eccezione di Westminster Abbey, solo perché lì venivano sepolti i grandi della nazione. Basti pensare all’abbazia di Canterbury, decisiva nel sorgere della nazione e distrutta del re per appropriarsi di pietre e travi.

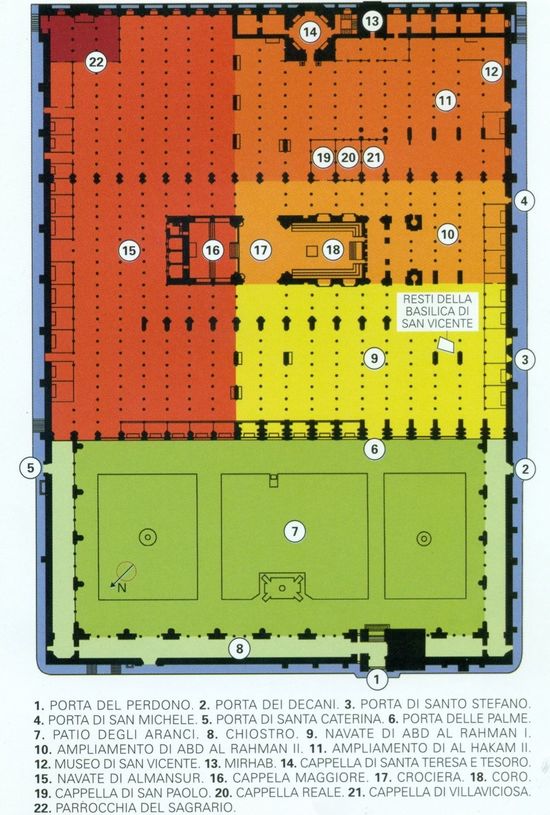

Andando più indietro nella storia, si pensi ancora alla distruzione della cattedrale di San Vincenzo di Cordoba (la Catedral-Mezquita-Catedral) o alle sinagoghe di Toledo e Cordoba costruite solo dopo che i musulmani furono sconfitti.

Ma, anche in positivo, nel “narrare” il passaggio dalla cultura latina a quella inglese si deve mettere in rilievo che la “fondazione” dell’Inghilterra e della stessa Londra è dovuta non ai “romani” pagani, bensì ai “monaci romani”, inviati da papa Gregorio Magno con sant’Agostino di Canterbury, che permisero il travaso dei due mondi e che fondarono le due abbazie di San Pietro (oggi Westminster) e di San Paolo (oggi St Paul’s Cathedral) quando i romani da decenni avevano abbandonato Londinium (interessantissimo è il fatto che la bandiera inglese rechi oltre alla croce di Cristo la croce di Sant’Andrea le cui reliquie vennero portate dai monaci). Lo stesso si deve dire della Germania, evangelizzata dai monaci, a partire da San Bonifacio, e integrata in una cultura ben più umanistica di quella dei suoi antenati.

Si pensi al silenzio assoluto sul periodo altomedioevale che è taciuto in ogni narrazione storica. L’emergere del potere temporale della Chiesa fu un evento provvidenziale e decisivo per Roma e per tutta l’Europa.

7/ Ricondurre la narrazione di un artista al suo tempo evidenziando la sua collaborazione con altri artisti ed il comune background

Importantissimo è che la “narrazione” mostri le relazioni esistenti fra i pittori della stessa epoca, così come il fatto che la committenza li obbligasse a lavorare insieme. I biografi di Caravaggio, ad esempio, si limitano a dire che al tempo c’erano diverse scuole pittoriche, tutte tese ad emergere una sull’altra. Ma di nessuna di esse gli autori antichi dicono che fosse disprezzata o sovra-esaltata per ragioni confessionali.

È interessantissimo che Caravaggio divenne famoso al grande pubblico per aver realizzato la Vocazione di Matteo il cui taglio di luce, provenendo non si da dove, cioè dalla grazia, giunge in un vicolo ad illuminare il volto di San Matteo, conferendo forza espressiva al braccio di Gesù che chiama.

Ebbene quella luce che irrompe nell’opera è in realtà una citazione – anche se una citazione per opposizione perché luce ed oscurità si invertono di posto - dell’affresco che il Cavalier d’Arpino aveva realizzato pochi anni prima nella stessa cappella Contarelli e che è visibile ancora oggi nella volta della Cappella. Anzi a quell’affresco potrebbe aver lavorato lo stesso Merisi come apprendista, poiché a Roma, in un primo momento, fu a servizio proprio del Cavalier d’Arpino.

Non solo, ma egli realizzò all’inizio solo le due tele laterali della Cappella, perché Jacob Cobaert, orafo e scultore, era stato incaricato contestualmente di realizzare la statua dell’evangelista che doveva essere posta sopra l’altare. Se l’opera non venne mai posta in opera nella Cappella Contarelli fu solamente perché la statua stessa non piacque al suo autore, oltre che ai committenti, e fu infine posta nella chiesa della SS. Trinità dei Pellegrini, motivo per il quale venne infine commissionata a Caravaggio anche la pala d’altare. Si vede subito che Caravaggio lavorò alla Contarelli in un programma iconografico la cui realizzazione era affidata, oltre che a lui, al Cavalier d’Arpino ed al Cobaert.

Se la Cappella Contarelli venne modificata in corso d’opera, portando alla presenza “casuale” di ben tre opere di Caravaggio nello stesso ambiente, diversamente avvenne nella Cappella Cerasi in Santa Maria del Popolo, che restituisce bene l’idea della collaborazione pittorica di artisti diversi e per altri aspetti rivali.

Nella Cerasi, la pala d’altare, cioè l’opera più importante, è di Annibale Carracci, mentre a Caravaggio, esattamente come nella Contarelli, venne affidata la decorazione delle due pareti laterali.

L’opera del Carracci, l’Assunta (1600-1601) è splendida e, probabilmente, fu anche il confronto con un opera così degna che dovette indurre Caravaggio ad abbandonare la prima versione della Conversione di San Paolo e della Crocifissione di Pietro, impari nel confronto, per realizzare quelle che sono attualmente in situ.

Interessantissimo è il caso della Deposizione dipinta da Caravaggio per la Chiesa Nuova – Santa Maria in Vallicella. Qui l’impianto iconografico venne deciso dallo stesso San Filippo Neri, ancora vivente, e dai suoi primi compagni . La pala d’altare di ognuna delle cappelle laterali doveva rappresentare uno dei “misteri”, cioè degli episodi più importanti della vita di Cristo, nei quali era stata presente Maria che doveva anch’essa essere rappresentata in ogni tela. Chiunque avesse deciso di acquistare una delle Cappelle laterali e di farle decorare – come usava allora – non si sarebbe potuto allontanare dalla serie stabilita dai Padri dell’Oratorio.

San Filippo Neri ebbe modo di vedere alcune delle opere già poste nelle Cappelle – è noto che l’opera da lui preferita era la Visitazione di Federico Barocci che venne realizzata nel 1586.

Nella Chiesa Nuova Caravaggio lavorò alla Cappella acquistata dalla famiglia Vittrici realizzando la Deposizione. Le pale d’altare dell’intero ciclo vennero realizzate dal 1578 al 1627 (senza contare le copie o le sostituzioni a programma completato, come avvenne proprio per la Deposizione che venne sostituita con una copia nel 1797 dopo il furto delle truppe napoleoniche).

Seguendo l’ordine iconografico, a partire dalla cappella del transetto sinistro, questo è l’elenco degli autori con le date proposte dagli studiosi:

- Presentazione al Tempio di Maria Bambina del Barocci (1603)

- Annunciazione del Passignano (1591)

- Visitazione del Barocci (1586)

- Natività di Durante Alberti (precedente al 1590)

- Epifania del Nebbia (1578)

- Presentazione al Tempio di Gesù (detta anche Purificazione della Vergine) del Cavalier d’Arpino (1627)

- Crocifissione del Pulzone (1586)

- Deposizione del Caravaggio (1602, originale presso i Musei Vaticani, mentre nella cappella è presente una copia del 1797)

- Ascensione del Muziano (precedente al 1587)

- Pentecoste di pittore fiammingo (originale del 1607 sostituito nel 1689)

- Assunta del Ghezzi (sostituita a metà seicento)

- Incoronazione della Vergine del Cavalier d’Arpino (1615).

Si vede qui chiaramente come la Deposizione del Caravaggio faccia parte di un intero ciclo pensato dai padri dell’Oratorio in pieno contesto controriformistico. Se ogni autore lavorò esclusivamente all’opera o alle opere che gli furono affidate, nondimeno doveva essere loro chiaro il lavoro d’insieme.

La serie della Chiesa Nuova permette di vedere come si regolassero i committenti e come si instaurasse un dialogo fra l’acquirente della Cappella, i Padri che officiavano la Chiesa Nuova e gli artisti.

È noto il caso della Crocifissione del Pulzone che venne realizzata ancora vivente San Filippo Neri. Uno dei primi compagni del Santo, il Padre Agnolo Velli, si lamentò per la presenza eccessiva di sangue che era rappresentato nell’opera, in particolare eccependo “una gocciola di sangue che cade sopra il volto del crocifisso”. I Padri dell’Oratorio misero democraticamente ai voti il particolare dell’opera, d’accordo con San Filippo Neri che non impose una propria scelta: la maggioranza approvò il modo in cui la tela era realizzata, motivo per cui non venne chiesto al Pulzone di modificarla.

L’episodio rivela come fosse stretto il rapporto fra committenza e artisti (fra l'altro il ciclo non si arresta alla serie delle dodici cappelle laterali, ma prosegue poi con la rappresentazione barocca dell'Assunzione di Maria nell'abside e nella cupola, ad opera di Pietro da Cortona, in una sequenza iconografica che travalica dal periodo controriformista appunto all'età barocca).

La critica moderna tende in maniera ideologica ad isolare dalla sua epoca Caravaggio, quasi come un unicum nel suo tempo, mentre egli dipingeva certamente conscio delle sue capacità, ma anche inserito pienamente con un suo stile particolare nella pittura della Roma controriformista del tempo.

Ciò è evidente anche dal lavoro dei suoi discepoli come da quello dei discepoli degli altri maestri di età controriformista. Negli anni seguenti la morte della generazioni di pittori cui apparteneva il Merisi, la nuova generazione si ispirò all’uno o all’altro dei maestri vissuti a cavallo fra la fine del cinquecento e gli inizi del seicento, fino all’esplodere dell’arte barocca.

Interessante è, per un diverso motivo, il caso della Madonna della serpe dove Caravaggio si attenne assolutamente alla presentazione dogmatica cattolica della figura di Maria. L’opera (che venne venduta solo perché nel 1605 iniziò la demolizione della navata costantiniana che allora era ancora in piedi) riprende modelli preesistenti e ben noti.

8/ Ricondurre ancora più radicalmente l’artista a quella narrazione voluta dalla committenza e chiarificatasi nei secoli per via della Tradizione

Non pochi pittori hanno dipinto le loro opere immaginandole in una serie. Famoso è il caso di Munch (Studio per una serie evocativa chiamata Amore, scelto per l’esposizione di Berlino del 1893 dove si descrive, infatti, la mutazione dell’amore dalla prima fase piena di speranza alla sua penosa fine. Il titolo viene poi mutato in Fregio: motivi della via di un anima moderna, per l’esposizione del 1904 a Kristiania, l’odierna Oslo, fino al più semplice Fregio della vita per Kristiania 1918).

Per le committenze ecclesiastiche l’unità è data non solo dalle scelte del singolo autore, ma molto più dall’unità della storia della salvezza (secondo quel principio di “unità” chiarificato dalla Dei Verbum al Concilio Vaticano II).

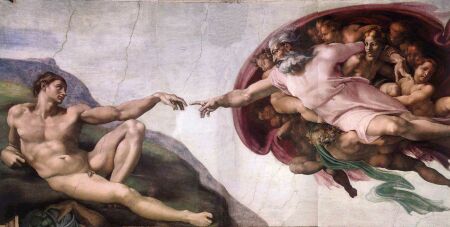

L’esempio più evidente in Roma è quello della Sistina dove la volta presenta la creazione, le pareti (dipinte precedentemente) la storia della salvezza e la parete d’altare il giudizio finale e la parousia. La Sistina – come la decorazione di ogni edifico antico – avvolge l’uomo con una narrazione globale. Se il post-moderno viene caratterizzato – a partire da Lyotard – come l’epoca della fine delle grandi narrazioni, ecco che invece la rappresentazione cristiana è ancorata in maniera irremovibile ad una narrazione talmente grande da abbracciare la storia intera.

A sua volta tale grande narrazione implica il principio interpretativo biblico della tipologia, uno dei principi più disattesi dalla catechesi oggi, ma saldo nella liturgia. Per la tipologia Isacco non è solo Isacco, ma è anche Cristo in figura, Mosè non è solo Mosè, ma è Cristo in ombra e così via. La “narrazione” biblico-artistica vive della tipologia, che ha fondamento nel popolo ebraico stesso e poi in Gesù. (cfr. «Il fatto che la liturgia abbia fatto sue e conservate lungo i secoli determinate esegesi tipologiche costituisce una specie di "consacrazione" di esse, tanto da poter essere considerate interpretazioni tradizionali e ufficiali della Chiesa». Al cuore della catechesi non c’è solo la Scrittura, ma anche la liturgia: solo la liturgia è in grado di “spiegare” la Scrittura attraverso la lettura tipologia della Bibbia. Tre riflessioni capitali di Sofia Cavalletti e gli altri articoli al tag tipologia).

La dimenticanza del senso complessivo delle immagini porta ad abbagli come quello cui spesso si assiste in San Francesco ad Assisi, dove nulla viene mai detto degli affreschi dell’abside o dei registri superiori della basilica, perché ci si sofferma unicamente sulle storie francescane (con danni per la presentazione del vero significato di Francesco d’Assisi e per la comprensione dell’effettiva evoluzione storico-artistica (il Maestro delle Storie di Isacco è molti più moderno di Giotto, pur essendogli precedente).

9/ La narrazione dei “misteri” come completamento offerto all’esegesi storico-critica

Anche da un altro punto di vista la rappresentazione iconografica ripresenta la prospettiva tipicamente teologica dell'unità della Scrittura. Mentre la lettura di un episodio neotestamentario può soffermarsi sulla prospettiva peculiare di un singolo evangelista, la rappresentazione dello stesso obbliga ad una sua riproposizione unitaria. Se si rappresenta il Battesimo di Gesù passa in secondo piano come lo descrivono i diversi evangelisti: l'artista si trova a dover essenzializzare l'evento.

Similmente Michelangelo non si pose il problema, nel rappresentare la creazione di Adamo, di mostrare le differenze fra il racconto di Genesi 1 e quello di Genesi 2, bensì elaborò un'immagine sintetica che non rispecchiava la lettera di nessuna delle due versioni, bensì le ricreava, fornendone un'interpretazione che è più toccante di qualsiasi studio biblico scientifico.

Questa prospettiva è particolarmente rispondente alla formazione di uno sguardo sintetico del credente, mentre la sottolineatura delle diverse sfumature è più pertinente per uno studio accademico.

In questa maniera l'iconografia mostra, a suo modo, la perenne validità della presentazione dei cosiddetti “misteri” di Cristo e, più in generale, dei “misteri” della storia della salvezza. Essa ricorda che, per chi vuole “vedere” la fede, non è pressante tanto la domanda sulla prospettiva che caratterizza, ad esempio, le diverse versioni dell’Ultima cena, quanto piuttosto la questione del significato intrinseco di quell'evento. Lo stesso dicasi perGenesi dove la grande questione che ogni persona porta in cuore riguarda la verità del racconto, se Dio abbia veramente creato l'uomo oppure no, se l'uomo abbia una dignità diversa dall'animale o no, cosa annunzi di incomparabilmente bello il fatto della creazione e come questa possa completare le moderne ricerche scientifiche. Un approccio puramente letterario alla questione sarebbe da un punto di vista artistico e catechetico assolutamente insufficiente.

10/ Narrare la storia della Chiesa

Abbiamo cercato di mostrare come sia non solo impossibile concretamente, pena l’abbandono di un atteggiamento oggettivo e scientifico, ma anche controproducente e pedagogicamente inefficace, separare l’arte dalla Chiesa e dalla sua storia.

Ma abbiamo sottolineato come la storia di cui qui si tratta non è l’attualità del tempo sempre cangiante – chi dipinge o costruisce in maniera troppo aderente alla moda ed ai problemi del tempo non è comprensibile nei secoli a venire – bensì l’attualità di un messaggio che tocca sempre i cuori, permanendo attuale.

È per questo che, ad esempio, una lettura troppo “contemporanea” – motivato dalla conversione al cattolicesimo, come si usa dire, del re francese Enrico IV - dell’inserzione di Pietro nella Vocazione di Matteo di Caravaggio non è credibile, sia perché darebbe adito ad ipotizzare un’ipocrisia del pittore, sia perché meschina e povera, rispetto al valore “eterno” della rappresentazione artistica. Molto più sensata è una lettura che inviti a superare la distanza fra il Cristo e i contemporanei di Caravaggio seduti al banco delle imposte.

II/ Andrea Lonardo. “Narrating the History of Art - Narrating the History of the Church”

(traduzione di Nicola Tassinari)

1/ What is the connection between History of Art and History (of the Church). Is artwork, and Christian artwork, a power instrument or an expression of life?

What narrations are told nowadays by guides accompanying tourists and pilgrims? What vision of the connection between History of Art and History of the Church emerges from their words?

A/ Certainly there is a spritualistic narration of art, when some christian communities set up very “self-righteus” instruments inviting to pass through St. Giovanni al Laterano in memory of Baptism and Profession of Faith, or pass through St. Peter’s Chair to thank for the Pope presence.

B/ But, even more, there is an introduction to art that’s wholly based on historical datings and philosophical considerations, according to mainstream culture’s criteria, refusing to say what a “classic” is, and which ones are the “values” of liberal arts. Fearing not to be scientific, often nowadays a guide just presents chronologies of buildings and works from Roman Empire to today.

Yet, often, in order to become interesting, and reach the imagination of pilgrims or tourists, such scientific narrations need to tell of spicy/sexual implications (as fairy-tales on Caravaggio’s models, or, in Baroque Age, tales on Olimpia Maidalchini, the so-called “Pimpaccia”); or they describe moralistically the corruption of Popes (from Alexander the Sixth to Julius the Second and Urban the Eighth or Alexander the Seventh), with continuous references to Inquisition, or insinuating the idea of Catholic Art as a propaganda, being used, for example, during Baroque Age as a “reconquista” of those losses due to protestant Reformation.

The unconscious passing from a scientific language to a moralistic one testifies the predominance of an ideological vision that is scientist and moralist at the same time.

C/ There is also a narration that sees the single artist as a free thinker, a rebel and misunderstood genius in an oppressive age (as Michealangelo or Caravaggio are usually introduced, for example). Indeed, there’s a narration that, once again, separates the work of art from the life of its own time because it doesn’t want to acknowledge the greatness and beauty of a certain epoch (being it the Middle Age, or Counter-Reformation, or Baroque).

A never openly-confessed idea often emerges behind such vision, and it’s that the history of the Church was nice just until Constantine, and then just after the Council: all the rest would be some kind of emptiness without Christ nor Spirit.

However, and even more deeply, behind this kind of approach in narrating the history of art, it’s evident the dependence on a materialistic reading of history. Everything is related to power issues, “propaganda”, with points of view that are imposed by establishment, ruling class, and members of the clergy in their own time. Everything is re-read in a dynamic of conquer of the public space through art.

The path of beauty (via pulchritudinis) implies that one should give up this perception of the artwork just as a super-structure of an underlying economical structure, or of power in any way, that would rather be its supportive meaning. As known, this is the materialistic conception, according to which a “path of beauty” shouldn’t even be possible, because culture would simply be the ideological cover created in each epoch to validate a certain power structure.

Indeed, a work of art that should simply hide different purposes from beauty itself, even if unintentionally, wouldn’t have any sort of beauty of its own. Particularly, it was Ricoeur that classified under the title of “masters of suspicion” the great three maîtres à penser of our time, Marx, Freud and Nietzsche. They’ve been able to be suspicious of every human expression, testifying in each what comes from an underlying fight over power - as for Marx -, from an unconscious that’s rooted in close parental relationships, particularly in sexual experience - as for Freud -, or yet from a super-man creativity that tries to give some meaning to the whole universe, which is in itself nihilistically lacking of it instead - as for Nietzsche. If their de-constructive critique still is an unavoidable task, nonetheless the question if everything may be reduced to such spurious intents still applies, and, even more, if the work of man - and artwork in specie - may not come from an original wish for good and beauty.

If, introducing single works of art or whole artistic periods, statements inspired by such visions do prevail, the artwork will then be analyzed in search of clues showing how it has been an instrument of power, or an object meant to manifest the vanity of the customer, layman or member of the clergy, that commissioned it: all of the artwork of a given period will consequently be characterized as propaganda suitable for imposing a specific vision of the world to contemporaries.

The narration of “beauty” assumes a different requirement. The Gospel shows itself in artworks, whether in masterpieces or in more popular products, because both personal and ecclesiastical faith bear the innate need to express themselves.

Beauty yields because the meeting with the Christ cannot help displaying, becoming not just word, but also fresco, music composition, building, liturgical furnishing, that creatively brings back to faith. There’s no other ultimate root in Christian artwork. Of course, super-structural influences, such as those reported by “masters of suspicion”, may intervene into history, even though they may never be the decisive element of Christian iconography, and they’ll have a limited place in historical-artistic introduction and in catechistic use of the works themselves.

With great wisdom F. Boespflug said about it: «I never believed in the theory of the need, based on an opposition between authority and believers. [...] I believe much more in what I would call the expressive dynamism of strong intuitions. A religion that is experienced in a deep manner by a society must then be expressed. And after the words, Christianity has conquered in a logical way different expressive deeds, from plastic arts to theatre, music and literature».

One can see, yet by this first hint, that each “guide” has to handle the history of the Church, in order to introduce its greatness, otherwise his/her message will be unappreciated.

One might say that, often, faith isn’t to be announced in a straight manner: faith is to be announced in an indirect way, through the vision of life that arises from it. The truth of faith is displayed in its ability to beget, to fecundate. Artistic expression is one of the truth-tests for Christianity, together with liturgy, theology, charity, marriage, love that brings children up, passion towards cosmos, and so on.

2/ The basic grounds: early Centuries, early Christian art and Constantine

The centrality of this issue emerges clearly from the analysis - and different interpretations - of the basic grounds of Christian art.

Faith’s expressive need is so innate that it appears quite earlier than Constantine turning point. It’s enough to see how records show that at the beginning of the Third Century - one Century before Constantine - Christian community already owned cemeteries. In Rome, where sources help the research, Callistus, deacon at that time, was charged with the care of catacombs, now named after St. Callistus, by Pope Zephirine. Community, even though persecuted by state public law, already owned common properties. Christian iconography of sarcophagus and catacomb frescos was already taking shape.

Even if it’s hard dating the transition from domus ecclesiae to first real churches, the building and decorating of specifically Christian buildings already was a fact halfway through the Third Century, as testified by Gallieno’s edict (in 262), also known as Restitution Edict, just because the Emperor decided upon giving back to Christians those properties they obviously had to have already owned previously. Only one Christian building of that period still survives, almost entirely preserved: it’s the famous church of Dura Europos, in today’s Syria.

The city was abandoned in 256, because of the coming of Sassanids and, then, all of its surviving monuments are earlier then that date.

Literary sources show that the case of Dura Europos certainly wasn’t the only one. We know from Eusebius of Caesarea that Emperor Aurelian (270-275), after the deposition of schismatic bishop Paul of Antioch, gave the church that was an Episcopal see to catholic bishop Domno. By documents of latin Africa relating Diocletian’s persecution it’s confirmed that in Abthugni (in today’s Tunisia) and in Cirta (in ancient Numidia, and today’s Algeria) there already were, earlier than 303, Christian basilicae.

When first donatist bishop Victor got to Rome itself from Africa, being sent there between 314 and 320, sources testify that, while he had no basilica where to gather his believers, Catholic Church had forty.

In Lactantius’ work it is even said that, when Diocletian’s persecution burst out, a basilica that was visible from Nicomedia’s Imperial Palace already existed, signalling that the existence of Christian buildings was by then an ordinary fact.

If the taking care and decorating of Christian buildings come first of Constantine turning point, it’s not less interesting the fact that they never come to a fall, not even in ecclesiastical movements that aimed to underline the charisma of poverty. It is well-known, for example, that not only did Francis of Assisi commit himself to the restoration of ruined and abandoned churches - San Damiano in primis - but he also wanted liturgical ornaments to be of a precious and not cheap material: «I beg you, more than if it was pertaining to myself, that, when it seems convenient and useful to you, you should supplicate the clerics that ought to venerate above all the holiest body and blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the holy names and His written words that sanctify the body. The chalices, corporals, ornaments of the altar and anything necessary to the sacrifice, ought to be of a precious material. And if in any place the Lord’s holiest body was to be put in a too miserable way, according to the Church’s command be it put in custody in a precious place, and be it carried with great veneration and administrated to others with discretion».

These facts testify that the existence of a Christian art has a different root from the aim to power.

3/ Every artist expresses not just himself, but his whole period: speaking of the greatness of an artist means also speaking of the greatness of the Church of his own time that appreciated him

History keeps on repeating itself since its beginning, before Constantine, e then with him. During the Middle Ages, in a supreme manner, big romanesque and gothic churches are due to people’s action.

An anti-christian author, Dario Fo, attemped to demonstrate that the Duomo of Modena has risen up in a period where there wasn’t any king nor bishop, to hide the fact that people always loved their own cathedrals, and yet that during the Middle Ages inside cathedrals there were actors and clowns, saints and scholars, men and women, sibyls and prophets, devils and dragons, and so on.

That’s why speaking of the Duomo of Modena doesn’t mean speaking of an exception, rather of the beauty of the Middle Ages, and not of any anti-catholic exception!

In a same way speaking of Michaelangelo Buonarroti means speaking of a man that, until the day of his death, worked to honour the memory of Julius the Second (the tomb that is “the Moses”), to honour the importance of the Law and of ministers sent from God (the Commandments and Moses himself), as well as he worked to St. Peter’s dome, without wanting to be paid, or to the decoration of Pauline Chapel, destined to popes’ Eucharistic adoration.

Same as above speaking of Caravaggio means exalting the Counter-Reformation age. Merisi loved Rome and, once he escaped because of a murder he committed, he did anything to get back there. In Malta he became Knight of the Cross, with the Pope’s consent, signing himself as frater “consacrated”.

Yet, cheating on the listeners, guides keep on repeating about the refusal of his works (see: the snake Madonna, with its centrality of Mary), ascribing every catholic fact to political events (see: insertion of the figure of Peter in St. Matthew’s Call), omitting of the centrality of the Scriptures in Counter-Reformation Church (Matthew the Evangelist), forgetting about devotions he depicted (Loreto’s house in the Pilgrim’s Virgin), overlooking clear quotes not just from Michaelangelo (Cappella Cerasi), but also from the masters of Humanism and Renaissance (Jacopo Sansovino).

Similarly when dealing with Baroque guides omit to explain its function and reasons of artistic choices. With regard to this, the meaning of St. Peter’s colonnade is clear (as is the frequent use of curved line, concave or convex). Some outlines of the same period show the awareness that men of Baroque Age had about its symbolic meaning. Pope Alexander the Seventh himself, who commissioned the colonnade, wrote that it was meant to remind of two arms «embracing catholics to confirm them into faith, heretics to reunite them to the Church, non-believers to illuminate them» (see the beautiful Lo spirito del barocco by Olivier de la Brosse O.P. on www.gliscritti.it ).

4/ Every work gets light from its historical-geographical position and its liturgical function

An artwork’s historical position is grounded in the narration not only of what characterizes a certain epoch of the Church’s history, but endures in time as a constant in faith and life of Church.

Church, indeed, is a public reality made up by men and women communicating each other through signs: without the use of proper signs Salvation would just be a private eventlacking any ecclesial substance.

Through the path of beauty (via pulchritudinis) we have to face the great objection modern man addresses to Christianity. Cardinal Ratzinger once stated in these terms:

«To us, contemporary men, the basic scandal of being-christian is represented first of all by the exteriority into which religious experience seems to be turned up. We’re scandalized by the fact that God has to be communicated through exterior devices: by means of the Church, sacraments, dogma, or even just through preaching (kerygma), behind which we gladly hide in order to lessen the scandal, remaining anyway something external. In front of all this, one asks himself: does God really live in institutions, events or words? Doesn’t the Eternal touch each of us inside? So, we have to answer at once and simply to this question, adding: if there were only God and a sum of single persons Christianity wouldn’t be necessary, […] For the single one’s Salvation it simply wouldn’t take any Church, nor history of Salvation, nor incarnation and passion of God in the world».

Man is a person provided not just with a spiritual nature, but also with a corporeity that constitutes him as a being in a relationship. This is why it wouldn’t have any sense to him a religion that should be purely internal. Ratzinger himself faces the question like this:

«Being given a corporeity necessarily involves communitarian history and life, since, if pure spirit may be conceived as strictly separate, corporeity testifies the descending from others: men live one by the other, in an extremely real sense and various as well».

Art shows us all this in a peculiar way. Great artistic creations almost always occurred with the involvement of the whole people of God. As an example, one may think of the big building sites of Romanesque and gothic cathedrals. Recent studies on the archives of Milan’s “Fabbrica del Duomo” (the institution that built and keeps on caring about the Duomo), for example, highlight how, in addition to rich families, single believers and even those who appear as most marginal categories in the community (as many prostitutes that freely gave their offerings for the building of Milan’s cathedral) contributed to the financing.

We shall never forget that tourists/pilgrims happen to see our churches when they are empty and they can’t perceive their use during big liturgies.

Telling about St. Peter’s colonnade means then telling of elections or funerals of Popos, or of blessings and hearings. Without the colonnade or the basilica, where else would we welcome Habemus Papam and first blessing? Where to ordain new priests? Or celebrate Baptism for catechumens? But, in the same way, how would it have been possible to save so many jews and refugees without those places? And who else might have mediated between Nazi and Allied ones in order not to place fights in Rome, without the existence of the State of Vatican itself? (see: June 4th, 1944)

Similarly Bernini’s Baldacchino, always remembered through silly quotation: “Quod non fecerunt barbari fecerunt Barberini” (“What the barbarians did not do, the Barberini did”), shouldn’t be remembered instead for its extraordinary way of attesting the centrality of Eucharist (and Baptism) for the people?

Let’s also think about the importance of “narrating” the liturgical position of artworks themselves. Caravaggio, for example, wanted to paint, “quoting” Michaelangelo, St. Peter that turns his head to watch the Eucharist while he’s been crucified (Cerasi and Pauline chapels).

5/ The importance of imagination

A guide’s task is that of telling and letting visualize the places as they were when they were first built, or at the time of events that took place there. St. Ignatius’s spiritual exercises and the experience of a pilgrimage to Holy Land or Franciscan places have been creating a consolidate tradition in this field, showing us which path to follow.

In front of St. Peter’s Square, for example, narrating means assuming the task of recalling Peter’s death and his burial, to show the extraordinary beauty and truth of his witness. To omit such “imagination” means to deny all of the meaning of the place itself.

In www.giubileovirtualtour.it we’ve made an attempt in using 3D techniques to strengthen this need for imagination (see also: La basilica di San Pietro in Vaticano: guida per la visita. I testi di www.giubileovirtualtour.it, di Andrea Lonardo).

St. Peter’s Square is the place to “recall” his martyrdom, but also the Pope’s election that gets life and meaning from it. For a foreign pilgrim it’s crucial “understanding through imagining” what he has seen many times on television, moving from virtuality to reality. The place adds the hic (“here, right here, in front of you”) to what he already knows.

We shall not forget that we’re supposed to tell about the birth of Christianity, or the announce of the Gospel in a given place, or the history of a certain saint (“ancient” Augustine or “modern” Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus or Madeleine Delbrêl)

In Rome I’m introducing the history of Christianity trough Fori Romani and Palatino, without holding myself to simple churches (see: Spiegare il Nuovo Testamento passeggiando per il Palatino ed i Fori imperiali. Una guida per la visita, di Andrea Lonardo).

6/ Overcoming the temptation of politically correct and saying a word about how the history we’re speaking of has changed the history of the Countries we’re living in

A narration of the history of arts according to effective “politically correct” standards hides many historical data in fear of looking intolerant towards non-catholics or anyway no-believers. Only of Christianity we’re used to speaking ill!

It is omitted that Van Gogh was a protestant preacher and that his first homily is kept.

It is omitted that Johannes Vermeer was a fervent catholic forced to live in Delft’s papist ghetto and that for him, as for members of Catholic Church, it was forbidden to celebrate the Mass in public, denying the “catholic” value of many of his works (see: “il Trionfo della fede”). In Sweden the catholic Mass will be allowed only from 1951.

It is omitted that, while Baroque Age’s theatre was developing in Italy, puritan England banished theatres, destroying them, and destroying also music instruments (theatre and music were considered diabolic), and in the Netherlands it was forbidden for jews to speak with Spinoza in Amsterdam’s synagogue because he had been declared heretic by rabbis (1656).

Going further back in history it is omitted that in England, starting from Henry the Eighth, all convents and monasteries were confiscated and destroyed, with the exception of Westminster Abbey, only because there were buried England’s great and famous ones. Let’s think about Canterbury Abbey, so crucial in the arising of the Nation and destroyed by the King to grab stones and beams.

One may also think about the destruction of St. Vincent’s Cathedral in Cordoba (Mezquita-Catedral, or Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba) or synagogues in Toledo and Cordoba that were built only after muslims’ defeat.

Yet, also in a positive perspective, when “narrating” the transition from Latin to English culture we have to highlight that the “foundation” of England and London itself is due not to pagan “Romans”, but rather to “roman monks”, sent by Pope Gregory the Great together with St. Augustine of Canterbury; they promoted exchanges between those two worlds and found both St. Peter’s Abbey (nowaday’s Westminster) and St. Paul’s (nowaday’s St. Paul’s Cathedral) many decades after Romans had abandoned Londinium (very interstingly, in addition to Christ’s Cross English flag bears the Cross of St. Andrew whose relics were brought by monks). the same should be said about Germany, evangelized by monks, starting from St. Boniface, and blent in a culture quite more humanistic than that of its forebears.

Let’s think about the absolute silence above Early Middle Age that’s omitted in every historical narration. The arising of Catholic Church’s temporal power was a providential event and a turning point for Rome and whole Europe.

7/ Bringing back the narration of an artist to his own time highlighting his collaboration with other artists and their common background

It is very important for “narration” to show existing relationships between painters of the same epoch, and also the fact that clients might compel them to work together. Caravaggio’s biographers, for example, just say that at that time there were many painting schools, all aimed to emerge from others. But authors never say if any of those schools was despised or over-exalted for religious reasons.

It is very interesting that Caravaggio became famous because of St. Matthew’s Call, in which light, coming from who knows where, as to say “from Grace”, reaches an alley to illuminate Matthew’s face, and giving expressive strength to Jesus’ calling arm.

So the light that bursts into the work is actually a quotation - even if a reverse quotation because light and dark trade their places - from the fresco made by Cavalier d’Arpino a few years before in the same Contarelli chapel, still visible nowadays in the chapel’s vault. Rather, Merisi himself might had worked to that fresco as an apprentice, since he just went to work by Cavalier d’Arpino when he was in Rome first.

Besides, he initially made only the two side paintings of the Chapel, because Jacob Cobaert, goldsmith and sculptor, had been charged with the evangelist’s statue that was supposed to be put above the altar. If the work has never been installed into Contarelli chapel it was only because neither the author nor the customers liked the statue, and finally it was put in Holiest Trinity of Pilgrims’ church (SS. Trinità dei Pellegrini), and that’s why it was then commissioned to Caravaggio also main altar’s painting. One can see at once that Caravaggio worked at Contarelli in an iconographic program handled with the help of Cavalier d’Arpino and Cobaert.

While Contarelli chapel has been changed during the work, leading to the “accidental” presence of three of Caravaggio’s works into the same space, things went differently inside Cerasi chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo, that represents a painting collaboration between different artists who might also be considered as rivals.

Into Cerasi chapel, the painting on the main altar, a sto say the most important work, is by Annibale Carracci, while the two side paintings were commissioned to Caravaggio, just like in Contarelli chapel.

Carracci’s work, “L’Assunta” (1600-1601) is wonderful and, probably, the comparison with such an artwork induced Caravaggio to leave his first versions of St. Paul’s Conversion and St. Peter’s Crucifixion, in favour of those in situ now.

Very interesting is the case of Deposition made by Caravaggio for the New Church (Chiesa Nuova - Santa Maria in Vallicella). Here the iconographical structure was decided by St. Philip Neri himself, when still alive, and by his first companions. Each side-chapel’s main painting should represent one of the “mysteries”, the most important episodes in Christ’s life, where Mary was there and she also had to be put in each painting. Anyone who should buy one of the side-chapels and make it decorate - as it was in the habit then - would not have been allowed to distance from the series set up by the Fathers of the Oratory.

St. Philip Neri could see some of the works already in the chapels - it is well-known that his best-preferred was the Visitation by Federico Barocci made in 1586.

In the Chiesa Nuova Caravaggio worked at the chapel bought by the Vittrici family creating the Deposizione. The altars’ central paintings of the whole series were made between 1578 and 1627 (not counting copies or substitutions to the program once completed, as with Deposizione substituted by a copy in 1797 after Napoleon’s troops stealing).

Following iconographic order, starting from left transept’s chapel, here’s the list of authors with dates suggested by academics:

- Presentazione al Tempio di Maria Bambina by Barocci (1603)

- Annunciazione by Passignano (1591)

- Visitazione by Barocci (1586)

- Natività by Durante Alberti (prior to 1590)

- Epifania by Nebbia (1578)

- Presentazione al Tempio di Gesù (also named Purificazione della Vergine) by Cavalier d’Arpino (1627)

- Crocifissione by Pulzone (1586)

- Deposizione by Caravaggio (1602, the original one is at Musei Vaticani, while in the chapel there is a 1797 copy)

- Ascensione by Muziano (prior to 1587)

- Pentecoste by a Flemish painter (1607 original, substitute in 1689)

- Assunta by Ghezzi (halfway through Seventeenth Century substitution)

- Incoronazione della Vergine by Cavalier d’Arpino (1615).

One may see clearly from here how Caravaggio’s Deposition is part of a whole series planned by the Oratory’s Fathers in a full Counter-Reformation context. Whether each author worked exclusively to the works assigned to him, nonetheless it should have been clear to them the project as a whole.

The Chiesa Nuova series enables us to see how customers behaved and what kind of dialogue there was between the Chapel’s buyer, the Chiesa Nuova’s Fathers, and artists themselves.

Well-known is the case of Pulzone’s Crucifixion that was painted while St. Philip Neri was still alive. One of the first companion of the Saint, Father Agnolo Velli, complained about the excessive portrait of blood in the work, particularly “one drop of blood falling on the face of the Crucified one”. The Oratory’s Fathers democratically expressed their opinion towards such detail in the work, upon an agreement with St. Philip who didn’t impose any choice: the majority approved the way the painting had been made, so no change was then asked to Pulzone.

The episode reveals how close the relationship was between customers and artists (furthermore the series isn’t just the twelve side-chapels but also the Baroque representation of Mary’s Assumption in the church’s apsis and cupola, made by Pietro of Cortona, in an iconographical sequency that runs indeed from Counter-Reform to Baroque).

Modern critics ideologically tend to isolate Caravaggio from his epoch, almost as a unicum in his own time, while he surely painted conscious of his own abilities, but also fully integrated with his peculiar style in Counter-Reform Rome of the time.

This is also evident from his pupils’ work as much as from the work of students of other Counter-Reform masters. In years after the death of those same generations of painters as Merisi belonged, the youngest generation got inspired by one or the other of the masters that lived between the end of Sixteenth Century and the beginning of the Seventeenth, until the bursting of Baroque art.

For a different reason, it’s interesting the case of the Madonna della Serpe (Madonna of the Snake) in which Caravaggio kept strictly to the catholic dogmatic presentation of the figure of Mary. The work (sold in 1605 only because of the demolition of the constantinian nave) reprises pre-existing and well-known examples.

8/ Bringing back the artist even more radically to the narration meant by the client and clarified during centuries by the Tradition

Many artists painted their works conceiving them as belonging to a series. It’s quite famous the case of Munch (Study for an evocative series called Love, chosen for Berlin’s 1893 Exhibition, where it is depicted the change from love’s first phase full of hope to its pitiful end. The title was then changed to Frieze: motives of the way of a modern soul, for 1904 Expo in Kristiania, today’s Oslo, until most simple Frieze of life for 1918 Kristiania).

For ecclesiastic clients the unity is given not just by the single author’s choices, but much more by the unity of the story of Salvation (according to the principle of “unity” clarified by Dei Verbum during Vatican II Council)

The most evident example in Rome is that of Sistine chapel where the vault shows the Creation, walls (painted previously) the history of Salvation and the altar’s wall the Final Judgement and Parousia. The Sistine chapel - as any decoration of ancient building - wraps up men in a global narration. If post-modern is characterized - starting from Lyotard - as the epoch of the end of great narrations, here it is instead the Christianity representation is anchored in unmovable way to such a great narration as to hold the entire History.

Such great narration implies the biblical interpretative principle of typology, one of the most neglected principles in today’s catechesis, but steady in liturgy. According typology Isaac isn’t just Isaac, but also Christ in figure, Moses non just Moses, but Christ in shades, and so on. Biblical-artistic “narration” lives on typology, that is rooted in the Jew people themselves and then in Jesus. (see: «Il fatto che la liturgia abbia fatto sue e conservate lungo i secoli determinate esegesi tipologiche costituisce una specie di "consacrazione" di esse, tanto da poter essere considerate interpretazioni tradizionali e ufficiali della Chiesa». Al cuore della catechesi non c’è solo la Scrittura, ma anche la liturgia: solo la liturgia è in grado di “spiegare” la Scrittura attraverso la lettura tipologia della Bibbia. Tre riflessioni capitali di Sofia Cavalletti and other issues on tag tipologia).

Forgetting about the overall meaning of images leads to mistakes like the one we often see in St. Francis of Assisi, where nothing is ever said on the apsis’ frescos or about the highest levels of the basilica’s walls, because we usually just stare at Franciscan stories (with damage for the introduction to the true meaning of St. Francis and the understanding of history of art’s actual evolution (the Master of Isaac’s Stories is much more modern than Giotto, although he’s been living previously).

9/ The narration of “mysteries” as a completion offered to critical historical exegesis

Even from another point of view the iconographic representation introduces once again the typical theological perspective of unity in Scriptures. While the reading of an episode in New Testament may linger on the peculiar perspective of a single evangelist, the representation of the same episode compels to one coherent proposal. If the Baptism of Christ is depicted it doesn’t matter how different evangelists describe it: the artist has to convey the episode to its basic essence.

Similarly Michaelangelo, in representing the creation of Adam, didn’t worry about showing the differences between the tale in Genesis 1 and that of Genesis 2, he just developed a synthetic image that didn’t reflect any of the two versions, but re-created them, giving of them an interpretation that’s more touching than any scientific biblical study.

This perspective is particularly fitting to the formation of a synthetic look of the believer, while the underlining of different shades is more relevant in an academic study.

In this manner iconography shows, in its own way, the everlasting validity of the presentation of the so-called “mysteries” of Christ and, more in general, of the “mysteries” in the history of Salvation. It reminds that, for those who wish to “see” faith, it isn’t that important the perspective relating, for example, different versions of Last Supper, rather it is the meaning of such event. The same about Genesis, where the big question is whether God created man, whether man has a different dignity from that of animals, or what Creation announces that is so beautiful and how it could complete modern scientific researches. A merely literary approach to the question would be absolutely useless both from an artistic and catechetic point of view.

10/ Narrating the history of the Church

We’ve tried to show how, separating art from the Church and its history, would be impossible in concrete, and damaging pedagogically; it would also mean giving up to being scientific and objective.

We’ve underlined how history we’re dealing with is not that of time, rather the effectiveness of a message that always touches hearts.

A reading too “contemporary” - as we use to say about the conversion to Catholicism of Henry the Fourth King of France - of Peter into St. Matthew’s Call isn’t reliable. Way too reasonable is a reading that goes beyond the distance between Christ and Caravaggio’s contemporaries that are sat at the taxes desk.

(traduzione di Nicola Tassinari)