La tradizione della Bibbia ebraica nel primo millennio/The hebrew Bible in the first millennium,

del prof Giuliano Tamani

Riprendiamo, per gentile concessione dell’autore e della dott. ssa Julia Bolton Holloway, dal sito

www.florin.ms l’articolo scritto dal prof.

Giuliano Tamani, docente di Lingua, letteratura e cultura ebraica e di Storia della filosofia ebraica presso

l’Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia. I neretti ed i titoli dei capitoletti sono nostri ed

hanno l’unico scopo di facilitare la lettura on-line

Il Centro culturale Gli scritti (23/1/2009)

Indice

I. La tradizione ebraica della Bibbia e le

antiche versioni

La documentazione sulla tradizione della Bibbia ebraica nella tarda antichità e nell’alto medioevo

è completamente diversa da quella delle sue traduzioni in greco, in latino, in siriaco, in armeno e in

copto. La differenza principale, che a prima vista può apparire sconcertante, consiste nel tempo che

intercorre tra la fine della composizione del testo ebraico e i suoi più antichi manoscritti, e fra

l’esecuzione delle traduzioni e i loro più antichi manoscritti.

Fra il secolo II a. C. – questo è il periodo in cui si ritiene che sia stata completata la Bibbia

ebraica – e il secolo IX d. C. – periodo al quale risalgono i più antichi manoscritti biblici

ebraici – c’è un vuoto di documentazione di quasi un millennio. Questa assenza di

documentazione è interrotta, ma solo apparentemente, dai manoscritti rinvenuti nelle grotte del Mar

Morto e databili ai secoli II a. C. – I d. C., i quali, se, da una parte, attestano la circolazione in

Palestina di libri biblici in forma di rotolo, dall’altra dimostrano che tali rotoli sono sopravvissuti

proprio perché nascosti, cioè sottratti alla diffusione.

Invece fra l’esecuzione delle traduzioni – ovviamente eseguite dopo la composizione della Bibbia

ebraica – e i loro più antichi manoscritti c’è un vuoto meno lungo e una documentazione

talora considerevole. Quattro-cinque secoli ci sono fra la traduzione greco-ebraica dei “Settanta”

(III-II a. C.) e i suoi più antichi manoscritti come il VATICANUS (sec. IV), il SINAITICUS (secc.

IV-V) e l’ ALEXANDRINUS (sec. V).

Tre secoli ci sono fra la traduzione siriaca eseguita dall’ebraico da cristiani o da ebrei nel

secolo II e nota come Peshitta e i suoi più antichi manoscritti come il Ms. Add. 14.425 della British

Library di Londra copiato nel 464 e come il CODEX AMIATINUS (secc. VI-VII).

Un secolo c’è fra la traduzione copta eseguita sulla base di quella greca dei

“Settanta” in Egitto nel secolo III e i suoi più antichi manoscritti che risalgono ai secoli

III-IV.

Quattro-cinque secoli ci sono fra la traduzione armena, eseguita nel sec. V sulla base dell’Esapla

di Origene, e i suoi più antichi manoscritti armeni (secc. IX-X).

Uno-tre secoli ci sono fra la Vulgata di San Girolamo eseguita a Betlemme nel 405-406 e i

suoi più antichi manoscritti come il TURONENSIS S. GOTIANI (secc. VI-VII), l’ AMIATINUS (secc.

VII-VIII), l’ OTTOBONIANUS (secc. VII-VIII), il CAVENSIS (secc. VIII-IX) e tre manoscritti del secolo IX

come il CAROLINUS , il PAULINUS e il VALLICELLIANUS .

Dal secolo VII si diffuse quasi esclusivamente la Vulgata di San Girolamo che, durante la rinascita

carolingia, fu accuratamente rivista da Alcuino abate nel monastero di Tours (797-801) e da Teodolfo vescovo di

Orléans (810). I principali centri di diffusione furono l’Italia, la Spagna, le isole anglosassoni e

la Francia. Secondo il repertorio Codices Latini Antiquiores di E. A. Loewe sono 280 i

manoscritti biblici anteriori al secolo IX. Dei novemila manoscritti del secolo IX esaminati da B. Bischoff

(secondo questo studioso essi rappresentano solo il 5% di quello che è effettivamente esistito) il 15%

è costituito da testi biblici e un altro 15% è costituito da commenti biblici.

Quali sono le cause di questo vuoto quasi millenario fra la fine della composizione della Bibbia ebraica e i

più antichi manoscritti medievali che l’hanno trasmessa? Le cause che di solito si propongono

per giustificare la non sopravvivenza di manoscritti ebraici, di contenuto biblico e non biblico, del Vicino

Oriente anteriori al secolo IX e dell’Europa anteriori al secolo XII sono normalmente queste:

-

Le vicende della diaspora, come le reiterate espulsioni e migrazioni degli ebrei e le frequenti

distruzioni dei loro beni.

-

L’assenza di istituzioni come i monasteri e le scuole delle cattedrali che, con i loro

scriptoria, hanno consentito la riproduzione e la conservazione dei manoscritti latini e di altre lingue. Ma

- si può obiettare - in alcuni paesi, come l’Italia ad esempio, le residenze degli ebrei sono

state abbastanza stabili. Inoltre, annesse alle sinagoghe, non c’erano talora scuole e luoghi di

studio?

-

Le disposizioni talmudiche che imponevano l’eliminazione, mediante sepoltura (talora addirittura

nelle tombe di venerati rabbini), dei libri logorati dall’uso che contenevano il nome di Dio, in

particolare dei rotoli della Legge (Sefer Torah ) e dei volumi destinati al servizio liturgico.

A quest’ultima causa, che mi pare la più verosimile, se ne può aggiungere

un’altra: la prassi, non regolamentata da nessuna prescrizione giuridica e rituale ma comunque

scrupolosamente seguita, di distruggere un manoscritto, magari consumato, dopo che ne era stata fatta una

copia.

Inoltre, per quanto riguarda i manoscritti biblici, si può con qualche fondamento pensare che, quando nei

secoli X-XI è stato riconosciuto come “canonico” il testo con i segni delle vocali e degli

accenti e con la masorah della scuola tiberiense della famiglia Ben Asher, tutti i testi

diversi da quello siano stati accuratamente eliminati per evitare letture differenti.

A questo processo di canonizzazione del testo biblico tiberiense recò un contributo fondamentale

Moshè ben Maimon, o Maimonide (Cordova 1138 – Il Cairo 1204), una delle più grandi

autorità del giudaismo medievale. Nel suo codice Mishneh Torah (La ripetizione della Legge),

composto in Egitto nel 1170-80, mentre espone le regole che si dovevano seguire per la scrittura del Sefer

Torah, Maimonide dichiara di aver adottato come modello un manoscritto biblico scritto da Ben Asher

senza indicare però il nome del copista (Sefer Ahavah, Hilkot Sefer Torah, 8, 1-4). Questo

esemplare, anche se i pareri degli esperti non sono unanimi, viene identificato con il CODEX ALEPENSIS che

sarà presentato fra poco. Sulla base dell’autorità di Maimonide il processo di canonizzazione

del testo biblico tiberiense si rafforzò ulteriormente fino a far diventare questo testo il textus

receptus della Bibbia nel Vicino Oriente ma soprattutto in Europa dove, fino a circa la metà

dell’Ottocento, non si ebbe alcuna conoscenza di esemplari biblici da esso diversi.

II. I più antichi manoscritti

conservatisi della Bibbia ebraica vocalizzata dai masoreti

Una ventina sono i manoscritti ebraici che sono anteriori al Mille e che contengono tutta la Bibbia o

parti di essa. Sono stati scritti nei secoli IX-X in Palestina, in Egitto e in Iraq con scrittura quadrata di

tipo orientale. Quasi la metà sono databili grazie al colophon o a note di possesso, mentre i rimanenti

sono databili su base paleografica.

Si presenta ora una decina di questi manoscritti che si distinguono per la qualità del testo, per

la loro decorazione, per il ruolo che essi hanno avuto, soprattutto nel Novecento, per l’edizione del testo

ebraico della Bibbia e per le vicende del loro ritrovamento e della loro conservazione.

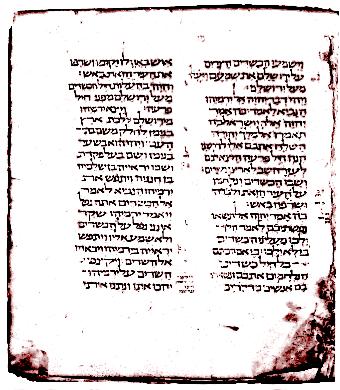

1. San Pietroburgo, Istituto di studi orientali

dell’Accademia delle Scienze della Russia. D 62.

Profeti posteriori con masorah magna et parva in forma compendiata

da C.B. Starkova, 'Les plus anciens manuscrits de la Bible dan la collection de l'Institut des etudes

orientales de l'Academie des Sciences de l'U.R.S.S.', in La paleographie hebraique medievale:

Colloques internacionaux du C.N.R.S. (Paris, 11-13 septembre 1972), Paris: Editions du C.N.R.S.,

1974, pl. VIII

|

Incompleto; contiene Isaia 37,20-43,7; 60,20 – Geremia 20,17; Geremia 32,12-52,21; Ezechiele e i Profeti

minori sono completi.

I segni delle vocali e degli accenti e la masorah secondo la terminologia babilonese non sono coevi al

testo ma sono stati aggiunti in un secondo momento.

Membrana molto spessa e rigida, sec. IX (847?), mm. 345 x 290, cc. 190 ma 191 per c. 32bis, scrittura quadrata

orientale, due colonne, linee 20.

Colophon incompleto: “Io l’ho scritto, Yishaq sofer Kahana […]”. Forse è il

copista che ha aggiunto la masorah.

Atto di vendita di Said […] ben Ya‘aqov con data 24 marheshwan 4608 (= 847); se questa data e

la sua lettura fossero esatte – i paleografi non concordano sulla loro esattezza anzi qualcuno ritiene che

il manoscritto sia posteriore di cinquanta o cento anni – questo sarebbe il più antico manoscritto

ebraico datato.

Legatura molto antica con piatti lignei.

Questo manoscritto è entrato nell’Istituto di studi orientali nel 1929-30 insieme ad altri

manoscritti della “grande sinagoga” degli ebrei di Karasubasar (Crimea) e insieme alla collezione

della Biblioteca Nazionale dei caraiti di Eupatoria.

2. CODEX PROPHETARUM CAIRENSIS

Il Cairo, Sinagoga caraita.

Profeti con i segni delle vocali e degli accenti e con la masorah magna et parva.

Membr., sec. IX (Tiberiade, 894-895?), mm. 200 c. x 200 c., pp. 586 secondo la riproduzione in facsimile,

scrittura quadrata orientale, tre colonne, linee 23.

Come risulta dal colophon, il manoscritto è stato copiato per Ya´bes ben Shelomò ha-Bavli (il

babilonese) da Moshè ben Asher, il padre del famoso masoreta Aharon, che vi ha aggiunto anche i segni

delle vocali, degli accenti e la masorah. Una nota posteriore ricorda che il manoscritto fu regalato alla

sinagoga degli ebrei caraiti di Gerusalemme, che nel 1099 i crociati, quando conquistarono Gerusalemme, se ne

impossessarono e che qualche anno più tardi David ben Yafet al-Iskandari (di Alessandria d’Egitto)

lo riscattò per donarlo alla sinagoga degli ebrei caraiti del Cairo dove è rimasto finora.

Decorano il manoscritto tredici “pagine tappeto” (dieci all’inizio e tre alla fine) riccamente

ornate con tabelle formate da complicati intrecci di figure geometriche (cerchi e quadrati), con rosoni formati

da motivi geometrici e floreali e da elementi architettonici combinati con motivi floreali. Si tratta di uno dei

più antichi esempi dell’arte decorativa islamica applicata a un libro.

Riproduzione in facsimile pubblicata a Gerusalemme nel 1971 con introduzione di D. S. Loewinger.

3. San Pietroburgo, Biblioteca Pubblica

Statale, Firkovich Bibl. II. B. 3.

PROPHETARUM POSTERIORUM CODEX BABYLONICUS PETROPOLITANUS

Profeti posteriori con i segni delle vocali e degli accenti secondo il sistema (sopralineare) babilonese e con

la masorah magna et parva.

In realtà, come ha dimostrato P. Kahle, il testo è stato vocalizzato secondo il sistema tiberiense

ma usando i segni-vocali del sistema babilonese.

Membr., sec. X (916), mm. 357 x 254, cc. 225, scrittura quadrata orientale, due colonne, linee 21.

Colophon a c. 224a.

Il manoscritto è stato trovato nel 1839 da Abraham Firkovich in una

genizah di Chufut-Kalè, in Crimea; fu acquistato nel 1863 dalla Biblioteca Pubblica Imperiale di San

Pietroburgo.

Riproduzione in facsimile a San Pietroburgo nel 1876 con introduzione di H. Strack e a New York nel 1971 con

Prolegomenon di P. Wernberg-Møller.

4. San Pietroburgo, Biblioteca Pubblica

Statale, Firkovich Hebr. II. *. B. 17.

Pentateuco con i segni delle vocali e degli accenti e con la masorah magna et parva

Membr., sec. X (Palestina o Egitto, 929), mm. 440 x 396, cc. 243, scrittura quadrata orientale, tre colonne,

linee 20.

Il manoscritto, come si legge nel colophon (c. 241a), purtroppo ora quasi illeggibile, è stato copiato

l’8 Kislew dell’anno 1241 dell’era dei Seleucidi (= 18 novembre 929): Shelomò ha-Levi

ben rabbi Buya’a (?) ha scritto il testo consonantico e suo fratello Efrayim ben Rabbi Buya’a vi ha

aggiunto i segni delle vocali e degli accenti e la masorah. I committenti sono rabbi Abraham e rabbi Tzaliah,

figli di rabbi Maimon. Shelomoh ha-Levi ben rabbi Buya’a è lo stesso copista che ha scritto il CODEX

ALEPENSIS che di solito viene datato intorno al 929 proprio grazie a questo colophon.

Il manoscritto è stato acquistato da A. Firkovich a Chufut-Kalè (Crimea).

La decorazione è costituita da otto “pagine tappeto”: quattro all’inizio, due

all’interno e due alla fine. La prima è decorata con palmette; la seconda contiene in forma molto

stilizzata la menorah con il turibolo e con i vasi; la terza contiene, sempre in forma molto stilizzata, il

disegno del santuario, della menorah, del paroket, della manna e di alcuni arredi sacri; la quarta contiene i

nomi dei due committenti scritti a caratteri quadrati molto grandi e circondati da cornici. Le altre quattro (cc.

64a, 65a, 241b-242) sono decorate con motivi geometrici eseguiti scrivendo in micrografia la masorah.

5. CODEX ALEPENSIS

Gerusalemme, Ben Zvi Institute.

Bibbia incompleta con i segni delle vocali e degli accenti e con la masorah magna et parva.

Contiene da Deuteronomio 28,17 a Cantico dei Cantici 3,11; mancano Ecclesiaste, Lamentazioni, Ester, Daniele e

Ezra; mancano alcune carte in Geremia, Profeti minori, II Cronache e Salmi.

L’ordine dei libri, diverso da quello elencato nel Talmud babilonese (Trattato Baba Batra 14b) è

identico a quello del CODEX LENINGRADENSIS .

In origine il manoscritto conteneva tutta la Bibbia ebraica e probabilmente era il più antico esemplare,

anche se non datato, del testo sacro; poi nel corso dei secoli per varie vicende un quarto del volume è

andato perduto.

Manca il colophon. Da una nota dedicatoria in arabo si apprende che il testo consonantico è stato scritto

da Shelomò ben Buya'a, lo stesso copista che nel 929 in Palestina o in Egitto ha copiato il ms. Firkovich

Hebr. II.*. B. 17, e che vi ha messo i segni delle vocali e degli accenti e la masorah il grande maestro

Aharon [ben rabbi] Moshè ben Asher, che è stato donato (metà del sec. XI?) dall’alto

funzionario […] Israel […] della città di Bassora ben mar Simhah […] a Gerusalemme

[…] per la comunità […] dei caraiti che abitavano sul monte Sion. Nel 1106 il manoscritto fu

trasferito presso la Keneset Yerushalayim della comunità degli ebrei caraiti di Misrayim, cioè di

un antico sobborgo del Cairo chiamato al-Fustat.

Molti ritengono, come è già stato ricordato, che questo sia il manoscritto biblico assunto come

modello da Maimonide nella redazione delle Hilkot Sefer Torah del Mishneh Torah.

Si ignora come e quando questo volume è stato portato presso la comunità sefardita di Aleppo, donde

il nome di CODEX ALEPENSIS . Ad Aleppo, come ad al-Fustat, al manoscritto erano attribuiti poteri miracolosi e lo

si considerava come un oggetto sacro. Portare olio per tenere accesa la fiamma della lampada della sinagoga che

custodiva il manoscritto, ad esempio, era ritenuto un privilegio. Per molto tempo, a causa del divieto dei capi

della comunità, esso non fu accessibile agli studiosi. Solo una pagina fu riprodotta nel 1877 in un

trattato sull’accentazione ebraica. Ad Aleppo il manoscritto rimase fino al 1948. Dopo la distruzione della

sinagoga, provocata da tumulti anti-ebraici, il manoscritto scomparve e fu dato per perduto. In realtà il

volume fu salvato, anche se privo di un quarto delle sue carte, fu portato in Israele e ora si conserva nel Ben

Zvi Institute di Gerusalemme.

Questo manoscritto, classificabile come codex vetustissimus o come codex optimus secondo i criteri

della critica testuale, fu oggetto di violentissime polemiche, di poco inferiori a quelle che accompagnarono la

scoperta dei manoscritti del Mar Morto. Le polemiche, basate quasi soltanto sull’unica pagina riprodotta e

sulla già ricordata nota dedicatoria in arabo, riguardavano l’autenticità della

vocalizzazione e della masorah di Aharon ben Asher, l’antichità del volume e la sua

appartenenza iniziale alla comunità degli ebrei caraiti, nonché l’adesione dello stesso

masoreta al caraismo. C’è, inoltre, chi sostiene che i colophon originali del copista e di

chi ha messo i segni delle vocali e la masorah siano stati eliminati.

Fino alla metà del Novecento solo Paul Kahle ne difese la sua appartenenza al gruppo dei manoscritti

prodotti dalla famiglia Ben Asher. Anzi, nel 1926 lo studioso tedesco voleva porlo alla base della sua terza

edizione della Biblia Hebraica (1929-37) curata da Rudolf Kittel. Ma il divieto posto dai capi della

comunità di Aleppo a qualsiasi impiego di questo manoscritto, lo indusse ad adottare il CODEX

LENINGRADENSIS .

Attualmente il CODEX ALEPENSIS, definito “The crowning of the master of the massora, Aharon ben Asher. The

codex considered authoritative by Maimonides. The sacred treasure of the ancient Jewish Communities of Aleppo", e

riprodotto in facsimile nel 1976 a cura di Moshè H. Goshen-Gottstein, sta alla base di The Hebrew

University Bible Project di Gerusalemme.

6. Londra, British Library, ms. or. 4445.

Pentateuco con i segni delle vocali e degli accenti e con la masorah magna et parva.

Incompleto: comprende da Genesi 39,20 a Deuteronomio 1,33.

Membr., sec. X1, mm. 165 x 130, cc. 186, tre colonne, linee 21, scrittura quadrata orientale.

Nelle note masoretiche ricorre spesso il nome del “gran maestro” (melammed ha-gadol) Aharon

ben Moshè ben Asher; questo significa che l’anonimo copista seguiva il suo sistema masoretico e che

ha copiato il manoscritto prima della morte del celebre masoreta perché il suo nome non è

accompagnato dalle consuete eulogie funebri. Sembra essere contemporaneo al CODEX ALEPENSIS . La scrittura

è simile a quella del PROPHETARUM POSTERIORUM CODEX BABYLONICUS PETROPOLITANUS del 916.

7. San Pietroburgo, Biblioteca Pubblica

Statale, ms. Firkovich Hebr. II. *. B. 39.

Profeti posteriori con i segni delle vocali e degli accenti e con la masorah magna et parva.

Membr., sec. X ([Gerusalemme], 988-989), mm. 456 x 375, cc. 151, tre colonne, linee 21.

Il manoscritto, come si legge nel colophon nonostante l’inchiostro sbiadito, è stato copiato,

vocalizzato, accentato e masoretizzato da un unico copista: Yosef ben Yaaqov ha-ma´aravi (= del Maghreb)

che ha avuto come modello gli esemplari di Aharon ben Moshè ben Asher.

8. Londra, British Library, ms. or. 9879

(già M. Gaster n. 150, o prima Bibbia della Collezione Gaster (1856-1939).

Bibbia completa con i segni delle vocali e degli accenti e con la masorah magna et parva.

Egitto, c. 1000. Decorato con motivi floreali nei margini e, talora, anche fra un versetto e l’altro;

alcune “pagine tappeto”.

9. Gerusalemme, Jewish National and University

Library, ms. Heb. 4° 5702 (già Sassoon 507).

Pentateuco con i segni delle vocali e degli accenti e con la masorah magna et parva.

Membr., sec. X [Tiberiade?], mm. 482 x 383, cc. 279, tre colonne, linee 20, scrittura quadrata orientale.

Questo volume è stato acquistato nel 1914 da David S. Sassoon (n. 1915) dai notabili della comunità

ebraica di Damasco, donde il nome “The Damascus Keter ” (La corona di Damasco); nel 1975

è entrato nella Jewish National and University Library di Gerusalemme.

Una riproduzione in facsimile è stata pubblicata nel 1982 a Copenhagen nella collana “Early Hebrew

Manuscripts in Facsimile” con introduzioni di R. Edelmann, D. S. Loewinger e M. Beit-Arié.

10. CODEX LENINGRADENSIS

San Pietroburgo, Biblioteca Pubblica Statale, ms. Firkovich Bibl. II. B. 19a.

Bibbia completa con i segni delle vocali e degli accenti e con la masorah magna et parva.

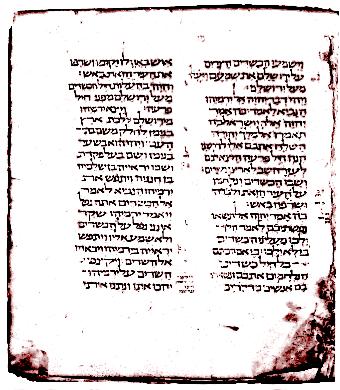

da B. Narkiss, Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts, Jerusalem, Keter Publishing House, 1969, c. 476b:

'pagina tappeto decorata con motivi geometrici e floreali e con micrografia', p. 44

|

È il più antico manoscritto ebraico completo e datato.

Membr., sec. XI (medinat Misrayim (= al-Fustat), 1008, 1009, 1010), mm. 338 x 298, cc. 491, scrittura quadrata

orientale, tre colonne, linee 27.

Colophon: copiato da Shemuel ben Yaaqov per Mevorak ben Yosef ha-Kohen. Secondo quanto si legge nel colophon il

copista l’ha corretto “secondo i libri molto esatti di Ben Asher”. Paul Kahle, ritenendo che

questo manoscritto sia una copia molto attendibile del testo biblico masoretico curato da Aharon ben Moshè

ben Asher, lo ha posto alla base della terza edizione (1929-37) della Biblia Hebraica curata da Rudolf

Kittel.

Per quanto riguarda la decorazione, con le sue sedici “pagine tappeto” questo manoscritto fra quelli

prodotti nel Vicino Oriente è uno dei più riccamente decorati. Lo schema prevalente nella

decorazione è costituito da archi, da figure geometriche e da motivi floreali colorati in oro, blu e

rosso. Gli spazi liberi sono stati riempiti con la masorah scritta in micrografia. In particolare, alle cc. 475b

e 476b sembra che sia stata raffigurata l’arca che conteneva il Sefer Torah.

Dettaglio con micrografia

|

Nel secolo XIV fu donato alla sinagoga degli ebrei caraiti di Damasco, come attestano alcune note di possesso in

arabo. Abraham Firkovich afferma di averlo acquistato proprio a Damasco. Nel 1862 è entrato nella

Biblioteca Pubblica Imperiale di San Pietroburgo.

Una riproduzione in facsimile è stata pubblicata a Gerusalemme nel 1971 con un’introduzione di D. S.

Loewinger.

III. Il ruolo di Abraham Firkovich

I quattro manoscritti che si conservano nella Biblioteca Pubblica Statale di San Pietroburgo provengono dalle due

raccolte che nel 1862-63 e nel 1876 furono vendute da Abraham Firkovich a questa biblioteca. Firkovich, nato

in Volinia nel 1786 e morto a Chufut-Kalè (Crimea) nel 1874, prima cantore ( hazzan)

nella sinagoga caraita del suo paese natale (Lutzk) poi mercante itinerante, si trasformò in

bibliofilo, archeologo e studioso. Durante i suoi viaggi in Palestina, in Siria e in Egitto, raccogliendo

più di diecimila manoscritti, costituì la più ricca collezione ebraica del mondo.

Sembra che Firkovich, animato dal proposito di provare l’antichità della presenza degli ebrei

caraiti nella Russia meridionale, non abbia esitato a modificare i colophon e ad alterare i testi per

raggiungere il suo obiettivo. Così il sospetto che alcune date siano state volutamente falsificate e che

alcuni testi siano stati aggiustati grava sui manoscritti delle sue raccolte. Ad incrementarlo hanno contribuito

le violenti polemiche scoppiate nella seconda metà dell’Ottocento fra i sostenitori del caraismo e i

suoi avversari. Il fatto che per molto tempo questi manoscritti non abbiano potuto essere esaminati dagli

studiosi non ha certo giovato a dissipare i sospetti e, soprattutto, a verificare l’autenticità dei

colophon e dei testi.

Tuttavia, al di là dei sospetti che riguardano alcuni manoscritti, resta comunque sempre consistente il

numero di quelli che sono databili ai secoli X-XII, come dimostrano, per rimanere in ambito biblico, i ventun

manoscritti elencati da Israel Yeivin nella sua introduzione alla masorah tiberiense pubblicata nel 1980 (Mevo

la-masorah tavranit.Introduction to the Tiberian Masorah. Translated and edited by E. J. Revell.

Published by Scholar Press (Missoula, Montana) for the Society of Biblical Literature and the International

Organization for Masoretic Studies).

IV. La tradizione masoretica e la famiglia

Ben Asher

La produzione di manoscritti biblici copiati in Palestina, in Egitto e in Iraq nei secoli IX-X si può

spiegare nel modo seguente.

A partire dal secolo VIII presso gli ebrei del Vicino Oriente, a causa di quella che Shelomo D. Goitein ha

chiamato la “rivoluzione borghese” (Ebrei e arabi nella storia , Roma, Jouvence, 1980, p. 120)

e a causa dell’influsso della civiltà islamica, iniziò un vasto processo di rinnovamento

culturale che coinvolse quasi tutte le discipline. Gli ebrei, in breve, passarono da una cultura

pressoché monotematica – quella che per comodità si può definire talmudica – a

una cultura politematica che si estendeva dall’esegesi biblica alla filosofia.

Uno degli effetti di questo rinnovamento fu la nascita degli studi sul testo consonantico della Bibbia

ebraica. Al sorgere e allo sviluppo di tali studi contribuirono l’esempio degli arabi che, con

l’aggiunta di segni vocalici, volevano fissare l’esatta pronuncia del testo consonantico del Corano e

dei cristiani orientali che, come gli arabi, volevano fissare l’esatta pronuncia dei loro testi in siriaco.

Vi contribuirono anche i caraiti (qara’im in ebraico, dalla radice qara’,

recitare, leggere, donde Miqra’, la lettura per eccellenza, cioè la Bibbia) cioè

quegli ebrei che, rifiutando la tradizione giuridica codificata nel Talmud, sostennero il ritorno alla sola

Bibbia, da interpretarsi letteralmente, come unica fonte di autorità. All’interno del mondo ebraico,

per la loro adesione alla sola scriptura, nella prima fase dello sviluppo del loro movimento che prese il nome di

caraismo, i caraiti sono considerati come i protestanti all’interno del cristianesimo.

Continuando, ampliando e perfezionando tentativi che sembrano essere stati iniziati nel secolo VII o poco dopo,

nei tre secoli successivi coloro che si dedicavano allo studio del testo biblico, in particolare i

naqdanim (lett.: puntatori, da niqqud, punto, in quanto furono impiegati in

prevalenza dei punti per indicare la maggior parte dei suoni vocalici), elaborarono almeno tre sistemi di

vocalizzazione: quello babilonese, elaborato in Iraq e chiamato anche sopralineare perché i segni

delle vocali venivano posti sopra le consonanti; quello palestinese, elaborato in Palestina, pure sopralineare,

ma che per indicare le vocali impiegava segni diversi da quello precedente; quello tiberiense, elaborato a

Tiberiade presso l’omonimo lago, che, nello stesso tempo, è sopralineare, sottolineare e

interlineare.

Quest’ultimo sistema, che è ritenuto essere la sintesi dei due precedenti e dei quali è

indubbiamente, pur nella sua complicatezza, il più perfetto, si affermò sugli altri e

diventò quello canonico. Oggi, quindi, si legge la Bibbia ebraica secondo il sistema di vocalizzazione

tiberiense, cioè secondo il sistema di pronuncia che è stato fissato dagli studiosi a Tiberiade

nei secoli VIII-X e che potrebbe riflettere la pronuncia dell’ebraico di quell’area e di quel periodo

e non, come ci si aspetterebbe, la fonetica dell’ebraico dell’antichità biblica.

Quasi contemporaneamente nelle stesse scuole, sulla base dei tre diversi sistemi di vocalizzazione, per fare

“una siepe intorno alla Torah” (masorah seyag le-Torah), cioè per fare in modo che il

testo sacro così fissato non subisse più modifiche, fu predisposto un complesso apparato di

osservazioni che fu chiamato masorah (lett.: tradizione), e che, scritto in aramaico, fu

registrato nei manoscritti a lato del testo (masorah parva), nei margini superiori e inferiori del testo

(masorah magna) e alla fine di ogni libro (masorah finalis).

La masorah parva è costituita da brevissime osservazioni che indicano la scriptio

plena e la scriptio defectiva di qualche parola, la ricorrenza di una parola nella Bibbia –

quindi l’hapax legomenon -, le espressioni caratteristiche e le forme simili che si trovano in altri

versetti. L’osservazione più funzionale alla lettura è l’errata-corrige, o

qere-ketiv ( ketiv indica lo “scritto” errato e qere indica la

“lettura” corretta), per mezzo della quale una parola o una frase scritta nel testo in modo errato

viene segnata con un cerchietto che rinvia alla lettura corretta posta nel margine. Ci sono quattro tipi di

correzione: 1) qere semplice, cioè “è scritto ma leggi”, quando si deve

correggere la lettura di una parola; 2) qere we-lo-ketiv, “leggi ma non è scritto”,

quando si deve introdurre una parola mancante; 3) ketiv we-lo-qere, “è scritto ma non

leggere”, quando si deve eliminare una parola superflua; 4) qere perpetuo quando, trattandosi di

parola molto frequente e nota (ad es.: Yerushalayim, il nome di Dio espresso con il tetragramma) si omette

la nota marginale e nel testo consonantico si inseriscono le vocali secondo cui la parola deve essere

pronunciata.

Nella masorah magna sono registrate tutte le varianti che sono state trovate collazionando

manoscritti autorevoli, comprese anche le minime differenze grafiche. Inoltre, a differenza della masorah

parva che riporta solo il numero della ricorrenza, sono indicati tutti i passi in cui ricorre una determinata

parola o espressione.

Nella masorah finalis, talora chiamata anche numerale e posta alla fine di ogni libro, si

registra il numero totale dei versetti di quel libro, delle parole, delle particelle, delle lettere

dell’alfabeto, nonché il versetto e perfino la lettera dell’alfabeto che si trova alla

metà del libro.

In assenza dei segni di interpunzione per facilitare la lettura furono introdotti anche i segni degli

accenti che hanno, com’è noto, tre funzioni: tonica, per indicare l’accento tonico di ogni

parola; pausale che equivale ai nostri segni di interpunzione; musicale, per indicare il modo recitativo della

lettura sinagogale. Ulteriori segni di accentazione si trovano nei libri poetici.

Si provvide anche alla divisione in versetti, in sedarim, in Parashot per il

Pentateuco e in Haftarot per i libri profetici.

Fra i vari sistemi masoretici si affermò, come sistema di vocalizzazione, quello tiberiense, in

particolare quello preparato dai membri della famiglia Ben Asher che furono attivi a Tiberiade dalla seconda

metà del secolo VIII per cinque o sei generazioni. Moshè ben Asher, vissuto nella seconda

metà del secolo IX, copiò, mise i segni delle vocali e degli accenti e la masorah al CODEX

CAIRENSIS , l’unico suo manoscritto autografo a noi giunto. Aharon ben Moshè ben Asher, suo

figlio, vissuto a Tiberiade nella prima metà del secolo X, fu l’ultimo studioso della famiglia e

quello più autorevole.

Egli mise i segni delle vocali e degli accenti e la masorah al CODEX ALEPENSIS il cui testo consonantico era

stato copiato da Shelomò ben Buya’a. Questo manoscritto, o altri alla cui copiatura lui aveva

contribuito, fu assunto come modello, come risulta dai colophon o come hanno verificato studiosi recenti, da

amanuensi posteriori. Si vedano, ad esempio, i Profeti posteriori copiati nel 989 (San Pietroburgo, Biblioteca

Pubblica Statale, Firkovich Hebr. II.*.B.39), il CODEX LENINGRADENSIS e il Pentateuco della prima metà del

secolo X conservato nella British Library di Londra (ms. or. 4445).

Alcuni studiosi sostengono che questa famiglia, o alcuni suoi membri, aderiva al caraismo. In realtà

Asher, il capostipite di questa famiglia, vissuto nella prima metà del secolo VIII era contemporaneo di

Anan ben David, il fondatore del caraismo. Aharon ben Moshè forse era un anziano contemporaneo di Saadyah

ben Yosef ha-gaon che proprio contro questa famiglia compose il trattato anti-caraita Essa meshali (edito

da B. Lewin e Sh. Abramson, Jerusalem, Mossad Ha-Rav Kook, 1943).

Il sistema dei Ben Asher, o il sistema tiberiense, grazie alla convalida di Maimonide, acquistò una

grandissima autorevolezza. Esso fu considerato canonico e gli altri sistemi scomparvero. Il sistema

tiberiense si diffuse, soprattutto in Europa, a partire dal secolo XIII. Fu riprodotto nei manoscritti dei secoli

XIII-XV.

Fu edito, a cura di Ya‘aqov ben Hayyim, nella seconda Bibbia Rabbinica stampata da Daniel Bomberg a

Venezia nel 1524-25. Fu ristampato, quasi sempre secondo l’edizione curata da Ya‘aqov ben Hayyim,

innumerevoli volte fino alle prime tre edizioni della Biblia Hebraica curata da Rudolf Kittel (1906, 1913,

1929-37). È stato nuovamente riproposto nella Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (1967-1977) ricorrendo

non più al testo di Ya‘aqov ben Hayyim ma al CODEX LENINGRADENSIS e nella Bibbia a cura di The

Hebrew University Bible Project di Gerusalemme che si basa sul CODEX ALEPENSIS (i tre volumi finora stampati

(1965, 1975, 1981) comprendono il testo di Isaia 1-44).

Il sistema dei Ben Asher, quindi, è l’unico che, a partire dal secolo XIII, fu accettato nella

Bibbia ebraica ma non si deve credere che la redazione stampata nelle comuni edizioni della Bibbia riproduca

esattamente quella di Aharon ben Asher. Le differenze che esistono fra i vari manoscritti e le edizioni a stampa

riguardano soprattutto la posizione degli accenti, del meteg in particolare, il diverso impiego dello

shewa e dello hatef in alcune forme grammaticali. Si tratta, comunque, di differenze che sono di

scarsa importanza per il lettore comune e che si sono formate nel corso degli anni, di solito come risultato di

interpretazioni grammaticali non sempre esatte.

V. La trasmissione della Bibbia ebraica in

Europa

In Europa la trasmissione della Bibbia ebraica prima del secolo XII è praticamente impossibile da

ricostruire. Infatti il più antico manoscritto biblico – Profeti anteriori e posteriori con

la traduzione aramaica attribuita ad Onqelos a versetti alternati - è stato copiato nel 1105 in area

ashkenazita o italiana. Esso appartenne all’ebraista cristiano Johann Reuchlin (1455 – 1522) e per

questo è noto come CODEX REUCHLINIANUS . Ora si conserva nella Badische Landesbibliothek di Karlsruhe (ms.

n. 3). Una riproduzione in facsimile, a cura di Abraham Sperber, è stata pubblicata a Copenhagen nel 1956

nella collana “The Pre-masoretic Bible” perché il curatore riteneva che il manoscritto

contenesse un sistema di vocalizzazione diverso da quello dei Ben Asher.

La maggior parte dei manoscritti biblici ebraici che sono stati copiati in Europa e che sono sopravvissuti

risalgono ai secoli XIII-XV. Come si spiega l’assenza di documentazione anteriore al secolo XII,

soprattutto se si ha presente che gli ebrei si trovavano in Europa fin dalla fine dell’era pre-cristiana?

Riesce difficile pensare che essi non avessero libri, o in forma di rotolo o in forma di codice, per il servizio

liturgico e per le esigenze della vita comunitaria. E, se li avevano, erano copiati in loco o erano importati dal

Vicino Oriente?

L’attività letteraria degli ebrei in Europa ci è nota a partire dal sec. X. Nella

Spagna islamica Hasday ibn Shaprut (915-970), medico rinomato al servizio dei califfi, era il mecenate della

scuola ebraica di Cordova per la quale si faceva spedire libri da Sura e da altre località del Vicino

Oriente. Nell’Italia meridionale Venosa, Otranto, Bari e Oria erano sedi di antiche comunità.

L’origine della comunità di Otranto viene fatta risalire agli ebrei deportati da Gerusalemme dopo la

sua distruzione del 70. d. C.; nella seconda metà del secolo X gli ebrei furono perseguitati e i loro

libri furono distrutti. La comunità di Bari raggiunse la sua massima fioritura nei secoli IX-XI. A Oria,

dove forse c’era un’antica scuola di copisti della Bibbia, alla fine del secolo VIII viveva un

copista di cui ci è stato tramandato il nome: Anatolios ben Sadoq detto ha-naqdan (il puntatore).

Sempre nell’Italia meridionale, ma a Capua, Shemuel ben Hananel (940-1008) fu amministratore delle finanze

dei signori locali, edificò luoghi di preghiera, restaurò la sinagoga edificata da un suo antenato

e fece copiare una gran quantità di libri.

Una delle poche testimonianze, se non l’unica, relativa all’esistenza di un manoscritto ebraico

biblico in Europa prima del secolo XII si trova nel Bereshit rabbati (La grande Genesi). In questa

compilazione midrashica, composta nella prima metà del secolo XI da Moshe ha-darshan di Narbonne, è

riportato un elenco di trentadue varianti che sono state riscontrate fra il testo masoretico e un antico Sefer

Torah che sarebbe stato conservato a Roma nella “sinagoga Severo”, così chiamata

forse in ricordo dell’imperatore Alessandro Severo (222-235) che con gli ebrei ebbe buoni rapporti. Nella

Biblia Hebraica curata da Rudolf Kittel queste varianti sono registrate come appartenenti al CODEX

SEVERI.

In Europa, come in parte si è già riferito, si diffuse il testo tiberiense. Per i secoli

XIII-XV manoscritti di riferimento per la loro riconosciuta qualità testuale ( codex optimus) sono

quelli scritti in Spagna: la Bibbia copiata a Toledo nel 1277 e conservata nella Biblioteca Palatina di Parma

(ms. parmense 2668 = De Rossi 782), la Bibbia copiata a Soria nel 1312 (dal nome del copista chiamata “Shem

Tov”; si tratta del manoscritto 82 della Collezione Sassoon che è stato venduto a un’asta di

New York nel 1984), e la Bibbia in tre volumi copiata a Lisbona nel 1482, riccamente miniata con motivi floreali

e conservata nella British Library di Londra (ms. or. 2626-28).

Questi ultimi due manoscritti stanno alla base dell’edizione curata, a partire dal 1958, da Norman Henry

Snaith per la British and Foreign Bible Society. Il curatore si è proposto di pubblicare un’edizione

senza apparato critico basandosi su alcuni manoscritti del basso medioevo ritenuti autorevoli dalla tradizione

(codex optimus). Questa edizione, recentemente ristampata in modo anastatico in Corea, ha tuttora una

discreta diffusione presso gli ebraisti soprattutto perché è facile da consultare.

Dalla prima metà del Cinquecento fino ai primi tre decenni del Novecento ebbe una grande diffusione

l’edizione, sempre basata sul sistema tiberiense, curata da Ya‘aqov ben Hayyim e stampata a Venezia

nel 1524-25 da Daniel Bomberg (la seconda Bibbia rabbinica per gli ebraisti cristiani, la prima Bibbia

rabbinica per gli ebrei). Il testo di questa edizione fu riproposto anche nelle prime due edizioni (Leipzig

1906, 1913) della Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia promosse dalla Società biblica di

Stoccarda e curate da Rudolf Kittel. Ma nella terza edizione (1929-37) il curatore, volendo pubblicare un testo

più antico di quello preparato da Ya‘aqov ben Hayyim nel 1524-25 e non essendo disponibile il CODEX

ALEPENSIS , utilizzò il CODEX LENINGRADENSIS che era di ben cinque secoli più antico. La Biblia

Hebraica curata da Rudolf Kittel - dal 1967 Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia - è una delle

edizioni più diffuse della Bibbia ebraica, soprattutto in Europa.

Breve bibliografia

P. Sacchi, 'Rassegna di studi di storia del Vecchio Testamento ebraico', Rivista di Storia e Letteratura

Religiosa 2 (1966) 257-324.

E. Würthwein, The Text of the Old Testament. An Introduction to the Biblia Hebraica, translated from

the German by E.F. Rhodes. SCM Press, London 1980.

Illuminations from Hebrew Bibles of Leningrad, Originally Published by B.D. Günzburg and V. Stassoff,

St. Petersburg 1886 - Berlin 1905. Introduction and new descriptions by B. Narkiss, The Bialik Institute - Ben

Zvi Printing Enterprises, Jerusalem 1990.

P. G. Borbone, 'Orientamenti attuali dell’ecdotica della Bibbia ebraica: due progetti di edizione

dell’Antico Testamento ebraico', “Materia giudaica” [rivista dell’Associazione

italiana per lo studio del giudaismo], VI/1 (2001), pp. 28-35.

See also Daniel Frank. Search Scripture Well: Karaite Exegetes and the Origin of the Jewish Bible Commentary

in the Islamic East. Leiden: Brill, 2004. Etudes sur le judaisme mediéval 29.

The hebrew Bible in the first

millennium,

prof. Giuliano Tamani, Università Ca' Foscari, Venezia

The documentation on the Hebrew Biblical tradition in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages is completely different

from its tradition in Greek, Latin, Syriac, Armenian and Coptic. The major difference, which at first seems

disconcerting, is in the timespan between the end of composing the Hebrew text and its earliest extant

manuscripts, from the carrying out of translations and their earliest extant manuscripts. From the second century

B.C.E. - which is the period when the the Hebrew Bible was completed - and the ninth century C.E. that is a gap

in the documentation of almost a millenium. This absence in the documentation is interrupted, but only

apparently, by the manuscripts discovered in the caves by the Dead Sea and dated from the second century B.C.E.

to the first C.E., which on the one hand, testify to the circulation in Palestine of Biblical books in the form

of scrolls, on the other show that such scrolls survived only because they were hidden, that is withdrawn from

circulation.

Instead amongst the translations, obviously carried out after the composing of the Hebrew Bible - and their most

ancient manuscripts is a far less large gap and a very considerable amount of documentation. There are only four

or five centuries between the Greek/Hebrew translation of the Septuagint (III-II B.C.E.) and the most ancient

manuscripts like the VATICANUS (IV), the SINAITICUS (IV-V) and the ALEXANDRINUS (V). There are only three

centuries between the Syriac translation made from the Hebrew by Christians or by Jews in the second century and

known as the Peshitta, and its earliest manuscripts, like the British Library's Add. 14,425, copied out in 464,

and like the CODEX AMIATINUS (VI-VII). There is only one century between the Coptic translation made from the

Greek of the Septuagint and its earliest suriving manuscripts which date to the III-IV centuries. There are only

four or five centuries between the Armenian translation made in the V century from Origen's Hexapla and

the earliest surviving Armenian manuscripts (IX-X). There are only one or two centuries between the

Vulgate carried out by St Jerome at Behlehem in 405-406 and the earliest surviving manuscripts such as the

TURONENSIS S. GOTIANI(VI-VII), the AMIATINUS (VII-VIII), the OTTOBONIANUS(VII-VIII), the CAVENSIS(VIII-IX) e

three IXth century manuscripts like the CAROLINUS , the PAULINUSand the VALLICELLIANUS.

From the VII century St Jerome's Vulgate circulated exclusively which, during the Carolingian Renaissance,

was carefully revised by Alcuin, Abbot of the Monastery of Tours (797-801) and by Theodulf, Bishop of Orleans

(810). The principles centres of distribution were Italy, Spain, the British Isles and France. In E.A. Loewe's

catalogue, Codices Latini Antiquiores, are 280 Biblical manuscripts prior to the IXth century. Of the nine

thousand manuscriptes Bernard Bischoff examined (who observes that these represent only about 5% of what once

existed) 15% are Biblical texts and another 15% are Biblical commentaries.

What are the reasons for this gap of almost a millennium between the completion of writing the Hebrew Bible and

the most ancient medieval manuscripts of it that survive? The reasons usually given for justifying the

non-survival of Hebrew manuscripts, of Biblical and non-Biblical content, from the Near East before the IXth

century and from Europe before the XIIth century are normally these:

1. The setting of the diaspora, with the repeated expulsions and migrations of the Jews and the frequent

destruction of their possessions.

2. The absence of institutions like the monasteries and the cathedral schools which, with their scriptoria,

permitted the copying and conservation of manuscripts in Latin and other languages. But - one could object - in

other countries, like Italy, for example, the residences of the Jews were sufficently safe. Indeed, annexed to

syangogues, weren't there also schools and houses of study?

3. The Talmudic requirement that required the elimination, through burial (sometimes even in the tombs of

venerated rabbis), of books worn from use containing God's Name, in particular the scrolls of the Law (Sefer

Torah) and volumes intended for liturgical use.

To this last cause, which seems to me the most likely, we can add another: the practice, not regulated by any

juridical requirement or ritual yet nevertheless scrupulously followed, of destroying a scarcely used manuscript,

after making a copy of it. Also, regarding Biblical manuscripts, one can consider with some basis that the text

recognised as 'canonical', because of its pointing with vowels and cantillation in the X-XI centuries and with

the masorah of the Ben Asher family of the Tiberian school, all other texts were carefully eliminated to

avoid different readings. This canonization process of the Tiberian Biblical text was fundamentally borne out by

Mose ben Maimon, Maimonides (Cordova 1138-Cairo 1204), one of the greatest authorities of medieval Judaism. In

his book Mishneh Torah (The Repetition of the Law), written in Egypt in 1160-80, while explaining the

rules that ought to be followed in writing the Sefer Torah, Maimonides stated he had adopted as model a

Biblical manuscript written by Ben Asher, without indicating the name of the copyist (Sefer Ahavah, Hilkot

Sefer Torah, 8, 1-14). This exemplar, although not all the experts agree, came to be identified as the CODEX

ALEPENSIS which will soon be discussed. On the basis of Maimonides' authority the canonization process of the

Tiberian Biblical text was so strengthened that finally it became the textus receptus of the Bible in the

Near East and above all in Europe where, until the middle of the nineteenth century, there was no knowledge that

there could be other Biblical exemplars.

There are twenty manuscripts dating before the year 1000 that contain all or part of the Bible. These were

written in the IX-Xth centuries in Palestine, in Egypt and in Iraq with square writing of the oriental type.

About half are datable because of the colophons or notes of ownership, while the others are datable on the basis

of the paleography. We will now present ten of these manuscripts which are distinguished for the quality of their

text, for their illumination, for the role that they have had, above all in the nineteenth century, in the

editing of the Hebrew text of the Bible and for circumstances of their discovery and their conservation.

1. St Petersburg, Institute for Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences. D 62.

Later Prophets with large and small masorah, added later according to Babylonian terminology.

IXth century (847? from date of sale), colophon of scribe adding masorah? Entered Institute 1929-30 with

other manuscripts from Synagogue of Karasubasar, Crimea.

2. CODEX PROPHETARUM CAIRENSIS

Cairo, Synagogue. Prophets with vowel and accent pointing and large and small masorah.

IX (Tiberiad, 894-895?), according to colophon, copied by Moshe ben Asher, father of famous masorete Aharon, who

added to it the vowel and accent pointing and the masorah . Later note says it was given to the Carait

Synaogue in Jerusalem, was taken by the Crusaders in 1099, then ransomed back and given to the Cairo Synagogue

where it still. Decorated with 13 'carpet pages', according to the models of Islamic book-art. The manuscript is

kept in the Karaite synagogue, in Cairo.

3. St Petersburg, Public State Library, Firkovich II. B. 3

PROPHETARUM POSTERIORUM CODEX BABYLONICUS PETROPOLITANUS

Later Prophets with vowel and accent pointing in the Babylonian style and with the large and small

masorah. Copied in Egypt in 916.Text vocalized in Tiberian system, though using Babylonian pointing. Found in

1839 by Abraham Firkovich in a genizah in Chufut-Kalè, Crimea. Purchased by Royal Library, 1863.

4. St Petersburg, Public State Library, Firkovich Hebr. II.*.B.17.

Pentateuch with vowel and accent pointing and with large and small masorah

Xth century (Palestine or Egypt, 929), copied by same scribe as of CODEX ALEPENSIS. Purchased by Firkovich,

Chufat-Kalè (Crimea). Decorated with 8 'carpet pages', some of which contain depictions of the Tabernacle

of the Ark.

5. CODEX ALEPENSIS

Jerusalem, Ben Zvi Institute.

Incomplete Bible with vowel and accent pointing and large and small masorah.

Copied in Egypt during the first half of the tenth century CE. After several transfers of ownership (from the

fifteenth century to 1948 it was in Aleppo, in the Sephardic synagogue; considered miraculous, scholars were

forbidden to consult it), today it is in Jerusalem, at the Ben Zvi Institute. The edition of The Hebrew

University Bible Project is based on this manuscript. It seems likely that this is the

“model”-manuscript Moshe ben Maimon consulted in Egypt in 1170-1180, when he wrote the Hilkot

Sepher Torah in his codex Mishneh Torah . Order of books differs from Babylonian Talmud, but is

identical withCODEX LENINGRADENSIS . Same scribe, Shelomò ben Buya'a, as 4. Once complete, has lost a

quarter of its contents.

6. London, British Library, ms. or. 4445

Pentateuch with vowel and accent pointing and with the large and small masorah

Incomplete, XIth century, masorah frequently cites then still-living 'great master' (melemmed ha-gadol ),

Aharon ben Moshe ben Asher. Contemporary with CODEX ALEPENSIS, writing like that of PROPHETARUM POSTERIORUM CODEX

BABYLONICUS PETROPOLITANUS of 916.

7. St Petersburg, Public State Library, ms Firkovich. II.*.B. 39

Later Prophets with vowel and accent pointing and with the big and small masorah

Xth century [Jerusalem, 988-990], copied, pointed and with masorah by one copyist using Aharon ben Moshè

ben Asher exemplar.

8. London, British Library, ms. or 9879

Complete Bible with vowel and accent pointing and with the large and small masorah

Egypt, circa 1000. Some carpet pages, floral marginalia.

9. Jerusalem, Jewish National and University Library, ms. Heb. 4° 5702

Pentateuch with vowel and accent pointing and with the large and small masorah

Xth century (Tiberiad?], formerly at Damascus.

10. CODEX LENINGRADENSIS , copied in Cairo in 1008-1010, preserved in Damascus from XIVth century, ornamented

with sixteen“carpet-pages”. As of 1876, in the State Public Library, in St. Petersburg. This is the

earliest dated Hebrew manuscript which contains the entire Bible. Therefore it was used as the basis of the third

edition (1937) of the Biblia Hebraica edited by R. Kittel, and published by the Württembergische

Bibelanstalt in Stuttgart.

These manuscripts reproduce with some differences, the Hebrew text with the masoretic vowels and accent apparatus

elaborated in Tiberias between the eighth and tenth centuries by scholars belonging to the Ben Asher family. For

instance, the CODEX PROPHETARUM CAIRENSIS was copied by Moshe ben Asher, the father of Aharon ben Moshe ben

Asher, purportedly the foremost scholar in that family: that Aharon ben Moshe ben Asher who wrote the vowels and

the masorah in the CODEX ALEPENSIS. After the year 1000 CE, only this “edition” of the Hebrew Bible

spread over the Near East, first, and then, over Europe. This text, edited according to the Tiberian vocalization

system and masorah, has preserved what is currently called the Tiberian Masoretic Text.

III

The four manuscripts conserved in the St Petersburg Public State Library come from two collections which in

1862-63 and in 1876 were sold by Abraham Firkovich to that library. Firkovich, born in Volinia in 1786 and died

in Chufut-Kalè (Crimea) in 1874, first Cantor (hazzan) of the Carait Synagogue of his native land

(Lutzk), then an itinerant merchant, transformed himself into a book lover, archeologist and scholar. During his

travels in Palestine, in Syria and in Egypt, he collected more than ten thousand manuscripts, forming the richest

Hebrew collection in the world. It seems that Firkovich, animated by the desire to prove the antiquity of the

presence of the Caraitic Hebrews in southern Russia, was not above modifying colophons and altering texts to

achieve his objective. So there is suspicion that some dates are willfully falsified and some texts are gravely

altered among the manuscripts of his collecting. In addition, the violent divisive polemics of the second half of

the nineteenth century between the supporters of Caraism and their adversaries aggravated the problem. The fact

that for a long time these manuscripts could not be examined by scholars has certainly not dispelled these

suspicions and, above all, to verify the authenticity of the colophons and the texts. Nevertheless, apart from

the suspicions concerning some manuscripts, the number of those which are datable to the X-XII, remains constant,

as was shown, in Biblical cirlces, the twentyone manuscripts selected by Israel Yeivin in his introduction to the

Tiberian masorah published in 1980 (Mevo la-masorah tavranit. Introduction to the Tiberian Masorah,

trans. and ed., E. J. Revell, Missoula: Montana: Scholar Press or the Society of Biblical Literature and the

International Organization for Masoretic Studies).

IV

The production of Biblical manuscript copied in Palestine, Egypt and Iraq in the IX-X centuries can be explained

in the following way.

From the VIII century among the Jews of the Near East, because of what Shelomo D. Goitein has called the

'bourgeois revolution' ( (Ebrei e arabi nella storia, Roma: Jouvence, 1980, p. 120) and because of the

influx of Islamic civilization, a vast process of cultural renewal began which involved almost all disciplines.

Jews, in brief, passed from a culture that was almost monothematic - which one could define for convenience as

Talmudic - to a polythematic culture which extended from Biblical exegesis to philosophy. One of the effects of

this renewal was the birth of the study of the consonantal text of the Hebrew Bible. The example of the Arabs

contributed to this beginning and development, who with the addition of vowel signs, wanted to fix the exact

pronunciation of the consonantal text of the Koran and of the Oriental Christians who, like the Arabs, wanted to

fix the exact pronunciation of their text in Syriac. To this the Caraits also contributed (qara’im

in Hebrew, from the root qara’, to recite, read, whence Miqra’ , the reading par

excellence , of the Bible), namely those Jews who, refusing the juridical tradition codified in the Talmud,

supported the return to the one Bible, to be interpreted literally, as the first phase of the development of

their movement which took the name of Caraism, Caraits in Judaism being considered as like Protestants in

Christianity.

Continuing, amplifying and perfecting experiments that seem to have been begun in the VIIth century or soon

after, through the three following centuries, in particular the naqdanim (literally, pointers, from

niqqud , point, which are used to indicate the greater part of the vowel sounds) dedicated themselves to

the study of the Biblical text, elaborating at least three systems of vocalization: the Babylonian, created in

Iraq and called even 'above line' because their signs for vowels came to be placed above the consonants; the

Palestinian, also 'above line' but in such a way as to indicate different signs than the preceding; the Tiberian

called so from Lake Tiberias, which at the same time, is above line, below the line and interlinear. This last

system, which is held to be a synthesis of the two preceding ones and which undoubtedly, despite its complexity,

the most perfect, was preferred to the others and bacem canonical. Today, therefore, one reads the Hebrew Bible

according to the Tiberian vocalization, which is according to the system of pronunciation fixed by scholars in

the Tiberiad in the VIII-Xth centuries and which could reflect the pronunciation of Hebrew of that area and that

period and not, as one would expect, the phonetics of the Hebrew of Biblical antiquity.

Almost contemporaneously in the same school, on the base of three different systems of vowels, to make 'a hedge

around the Torah' (masorah seyag le-Torah), that is to make it so that the sacred text so fixed could not

be further modified, there came to be put in place a complex apparatus of observations which were called

masorah (literally, tradition), and which, written in Aramaic, were recorded in the manuscripts at the

side of the text ( masorah parva , small masorah), in the top and bottom margins of the text

(masorah magna, large masorah) and at the end of every book of the Bible (masorah

finalis).

The small masorah is made of the briefest observations which indicate the scriptio plena and the

scriptio defectiva of each word, the recurrence of a work in the Bible - thus the hapax legomenon

-, the characteristic expressions and the similar forms found in other verses. The most functional observation to

the reading is the error correction or qere-ketiv ( ketiv indicates the 'written' error and

qere the correct 'reading'), by means of which a written word or phrase in the text that is wrong comes to

be signed with a circle that sends the reader to the correct reading placed in the margin. There are four types

of correction: 1) simple quere , that is 'is written but read' when one must correct a letter of a word;

2) qere we-lo-ketiv, 'read but not written', when one must introduce a missing word; 3) ketiv

we-lo-qere, 'is written but not read', when one must eliminate a superfluous word; 4) perpetual qere

when, treating of frequent and noted words (such as Jerusalem, the Name of God expressed with the

Tetragrammaton) the marginal note is omitted and in the consonantal text the vowel is inserted according

to how the word ought to be pronounced.

In the large masorah are give all the variants which are to be found in collating authoritative

manuscripts, including even the most minimal graphical differences. Moreover, different from the masorah parva

that reports only the number of recurrences, here are indicated all the passages in which a particular word or

expression recurs.

In the masorah finalis , also called numerale and placed at the end of each book, is listed the

total number of verses of that book, of the words, of the particles, of the letters of the alphabet, and also the

verse and even the letter of the alphabet which is found at the middle of the book.

In the absence of punctuation signs to help the reading were introduced also the signs of the accents which have,

as already noted, three functions: tonal, to indicate the tonic accent of each word; pausal, who is equivalent to

our punctuation signs; musical, to indicate the recitative mode of the synagogal reading. Further accentual signs

are found in the poetic books.

A division into verses is also provided, in sedarim; in Parashot for the Pentateuch and in

Haftarot for the prophetic books.

Among the various masoretic systems is chosen, as system for indicating vowels, the Tiberian, in particular that

prepared by the members of the Ben Asher family who were active in the Tiberiad during the second half of the

VIIIth century for five or six generations. Moshè ben Asher, living in the second half of the IXth

century, copied, putting in the vowel pointing, the accents and the masora , the CODEX CAIRENSIS, the one

autograph manuscript that has come down to us. Aharon ben Moshè ben Asher, his son, living in the Tiberiad

in the first half of the Xth century, was the last scholar of the family and the most authoritative. He put in

the vowel and accent pointing and the masorah to the CODEX ALEPENSISwhose consonantal text had been copied by

Shelomò ben Buya’a. This manuscript, or others to whose copying he had contributed, were taken as

model, as is shown by the colophons and as has been verified recently by scholars, by later copyists. This can be

seen, for example, in the Later Prophets copied in 989 (St Petersburg, Public State Library, Firkovich Hebr.

II.*.B.39), the CODEX LENINGRANDENSIS and the Pentateuch of the first half of the Xth century kept in the London

British Library (ms. or 4445).

Some scholars hold that this family, or some of its members, agreed with Caraism. In reality, Asher, the head of

this family, living in the first half of the VIIIth century was a contemporary of Anan ben David, the founder of

Caraism. Aharon ben Moshè perhaps was an older contemporary of Saadyah ben Yosef ha-goen who composed the

anti-Carait treatise Essa meshali against this family (ed. B. Lewin and Sh. Abramson, Jerusalem: Mossad

Ha-Rav Kook, 1943).

Ben Asher's system, or the Tiberian system, thanks to the validation by Maimonides, acquired the greatest

authority. It was considered canonical and the other systems disappeared. The Tiberian system spread, above all

in Europe, from the XIIIth century. It was reproduced in the XIII-XVth century manuscripts. It was edited by

Ya‘aqov ben Hayyim, in the second Rabbinical Bible printed by Daniel Bomberg in Venice in 1524-25. It was

reprinted, as always according to the system of Ya‘aqov ben Hayyim, innumerable times until the first three

editions of the Biblia Hebraica edited by Rudolf Kittle (1906, 1913, 1929-37). It was reproposed for the

Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (1967-1977), which resorted not to the Ya‘aqov ben Hayyim text but to

the CODEX LENINGRADENSIS and in the Bible edited by The Hebrew University Bible Project that is based on the

CODEX ALEPENSIS (the three volumes so far printed (1965, 1975, 1981) give the text of Isaiah 1-44.

Ben Asher's system, therefore, is the only one that, from the XIIIth century, was acceptable for the Hebrew Bible

but one should not consider that the printed editions of the Bible reproduced exactly that of Aharon ben Asher.

The differences that exist between the various manuscripts and the printed editions regard above all the position

of the accents, of the meteg in particular, the different uses of shewa and of hatef in some

grammatical forms. It involves therefore differences which are of little importance for the common reader and

which were formed over the course of many years, usually as the result of grammatical interpretations that were

not always correct.

V

In Europe the transmission of the Hebrew Bible before the XIIth century is practically impossible to reconstruct.

In fact the most ancient Biblical manuscript - Earlier and Later Prophets with the Aramaic translation

attributed to Onquelos in alternating verses - was copied in 1105 in an Ashkenazic or Italian region. It came

to belong to a Christian Hebraist, Johannes Reuchlin (1455-1522) and for this is known as CODEX REUCHLINIANUS.

Today it is kept in the Badische Lanesbibliothek of Karlsruhe (ms n. 3). A reproduction in facsimile, edited by

Abraham Sperber, was published in Copenhagen in 1956 in the collection, 'The Pre-Masoretic Bible' because the

editor believed that the manuscript contained a system of vocalization differnt from that of Ben Asher.

The greater part of Hebrew Biblical manuscripts that were copied in Europe and which survive are from the XIII-XV

centuries. How do we explain the absence of documentation before the XIIth century, above all when the Jews had

been present in Europe since the end of the Pre-Christian era? It would be difficult to believe that they had not

had books, either as scrolls or as codices, for liturgical services or for the needs of the communal life. And,

if they had them, that they were copied there or were imported from the Near East?

Literary activity amongst Jews in Europe is noticeable from the Xth century. In Islamic Sapin Hasday ibn Shaprut

(915-970), renowned physician in the employ of caliphs, was the Maecaenas of the Hebrew school of Cordova, for

which he had books sent from Sura and from other localities in the Near East. In southern Italy, Venosa, Otranto,

Bari and Oria were the sites of ancient Jewish communities. The origin of the Otranto community came about from

the Jews deported from Jerusalem following its destruction in 70 CE; in the second half of the Xth century the

Jews were persecuted and their books destroyed. The Bari community reached their greatest flowering in the IX-XI

centuries. At Oria, where perhaps there was an ancient school of Biblical copyists, at the end of the VIIIth

century there lived a copyist of whom we only have the name: Anatolios ben Sadoq called ha-naqdan (the

Pointer). Still in southern Italy, but at Capua, Shemuel ben Hananel (940-1008) was administrator of finances for

local lords, built places of prayer, restored the synagogue built by an ancestor and had a great number of books

copied.

One of the rare witnesses, if not the only one, about the existence of a Hebrew Bible manuscript in Europe before

the XIIth century is found in the Bereshit rabbati (the Great Genesis). In this Midrashic compilation,

composed in the first half of the XIth century by Moshe ha-darshan of Narbonne, is given a list of thirty two

variants which had been taken from the masoretic text and an ancient Sefer Torah that had been kept in Rome at

Severus' Synagogue, so called perhaps in memory of the Emperor Alexander Severus (222-235) who had good relations

with the Jews. In the Biblia Habraica edited by Rudolf Kittle these variants are given as from the CODEX

SEVERI.

In Europe, as we have already partly shown, the Tiberian text spread. In the XIII-XV centuries manuscripts known

for their recognized textual quality (codex optimus) were those written in Spain: the Bible copied at Toledo in

1277 and conserved in the Palatine Library in Parma (ms. parmense 2668=De Rossi 782), the Bible copied at Soria

in 1312 (from the name of the copyist called the 'Shem Tov'; which became Sassoon Collection ms 82, that had been

sold at auction in New York in 1984), and the Bible in three volumes copied at Lisbon in 1482, richly illuminated

with floral motives and conserved in the British Library, London ( ms. or 2626-28).

These last two manuscripts are at the base of the edition, from 1958, carried out by Norman Henry Snaith for the

British and Foreign Bible Society. The editor planned publishing an edition without critical apparatus, based on

some manuscripts of the late Middle Ages held to be authoritative in the tradition (codex optimus). This edition,

recently issued as a 'reprint' from Korea, has always had a sufficient distribution amongs Hebraists above all

because it is easy to consult.

From the first half of the sixteenth century until the first three decades of the twentieth century a great many

editions have been published, always based on the Tiberian system, edited by Ya‘aqov ben Hayyim and printed

in Venice in 1524-25 by Daniel Bomberg (the second rabbinical Bible for Christian Hebraists, the first rabbinical

Bible for Jews). The text of this edition was taken up again in the first two editions (Leipzig, 1906, 1913) of

the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia promoted by the Bible Society of Stuttgart and edited by Rudolf Kittel.

But in the third edition (1929-37) the editor, wanting to publish an earlier text than that prepared by

Ya‘aqov ben Hayyim in 1524-25 and not having access to the CODEX ALEPENSIS, used the CODEX LENINGRADENSIS

which was earlier by five centuries. The Biblia Hebraica, edited by Rudolf Kittel - from 1967 Biblia

Hebraica Stuttgartensia - is one of the most widespread Hebrew Bible editions, above all in Europe.

Bibliography

P. Sacchi, 'Rassegna di studi di storia del Vecchio Testamento ebraico', Rivista di Storia e Letteratura

Religiosa 2 (1966) 257-324.

E. Würthwein, The Text of the Old Testament. An Introduction to the Biblia Hebraica, translated from

the German by E.F. Rhodes. SCM Press, London 1980.

Illuminations from Hebrew Bibles of Leningrad, Originally Published by B.D. Günzburg and V. Stassoff,

St. Petersburg 1886 - Berlin 1905. Introduction and new descriptions by B. Narkiss, The Bialik Institute - Ben

Zvi Printing Enterprises, Jerusalem 1990.

P. G. Borbone, 'Orientamenti attuali dell’ecdotica della Bibbia ebraica: due progetti di edizione

dell’Antico Testamento ebraico', “Materia giudaica” [rivista dell’Associazione

italiana per lo studio del giudaismo], VI/1 (2001), pp. 28-35.

See also Daniel Frank. Search Scripture Well: Karaite Exegetes and the Origin of the Jewish Bible Commentary

in the Islamic East. Leiden: Brill, 2004. Etudes sur le judaisme mediéval 29.

[Approfondimenti]